By Clark Ricks

Waterproofing membranes are a critical component for keeping basements dry, but they’re only half the solution.

In most areas of the country, a complete drainage system should also be installed to relieve hydrostatic pressure and extend the life of the waterproofing membrane.

A system typically has three major components: a drainage board or membrane to give moisture an easy path down to the footings, a footing drain that directs water away from the structure, and either a sump pump, French drain, or stormwater collection system to dispose of the water collected.

The precise design of the system depends on the source of the water and the slope of the lot.

In some areas high water tables are the biggest concern. When the groundwater level rises higher than the level of the floor, the basement acts like a boat in a pond, and water will leak through any crack or hole in the concrete, or even through the matrix itself. If water is coming up through cracks in the floor, or water comes in at multiple locations, a high water table is to blame.

In other regions, surface water is a major concern. Significant rainfall, especially when combined with improperly installed rain gutters and downspouts, can put large quantities of water in direct contact with the house’s foundation. A poorly sloped lot can have the same effect.

Some builders believe that a dry climate or sandy soil makes drainage systems unnecessary, but this is usually not the case. Sprinklers, improper landscaping, or the occasional torrential rainstorm can all create leaky basements in desert communities.

An undrained or poorly-drained basement can create numerous problems. Without protection, waterproofing membranes can be damaged during the backfill process, or they can break down over time due to groundwater and soil chemicals. Damp walls conduct interior heat into the ground and moisture will damage belongings. Wet basements also contribute to mold growth, which has led to a flurry of lawsuits in recent years. In extreme cases, poor drainage can lead to structural failure of the wall.

The culprit behind nearly all leaky basements is hydrostatic pressure. The weight of water pressing outwards is dependent on its depth. Water 12 inches deep exerts only ½ pound per square inch, but at the bottom of an 8-foot basement, that adds up to 500 pounds per sq. ft! Engineers have calculated that the load on an undrained wall is often double that on a properly drained wall. Even if the wall can withstand the load, the pressure will drive the water through seams in the waterproofing and cracks in the concrete.

A good drainage system relieves this pressure, extending the life of the wall, the waterproofing materials, and the contents of the below-grade space.

Drainage Boards

Since the days of the Roman Empire, engineers and builders have used crushed stone or gravel as drainage. It’s usually cheap, readily available, easy to use, and works well when installed correctly. The principle is that water can flow through the airspace in the aggregate. A perforated pipe or drainage tile is installed near the footing, which collects the water and directs it away from the structure.

The drawback to these “aggregate drains” is that they require careful installation, and can sometimes clog with soil.

Beginning in the 1960s, other materials became available. Plastic sheet goods and geotextile fabrics gave waterproofing contactors new options for creating drainage systems.

Today, these so-called “sheet drains,” are available in a wide range of sizes, compressive strengths, flow rates, filtration capabilities, and chemical resistance to suit virtually any drainage application.

Delta MS, made by Cosella-Dorken, is typical. Made from high-density extruded polyethylene, the product has a series of dimples molded into the plastic that create an air gap between the membrane and the foundation. Designed primarily for residential applications, the product provides outstanding compressive strength and impact resistance (Just over 5,200 psf). It has been approved by the ICC for stand-alone use as a waterproofing membrane.

Dimple membranes are made by at least half a dozen other companies, including CCW MiraDRAIN by Carlisle Coatings & Waterproofing, Platon by Armtec, and GeoMat by MarFlex. SuperSeal and DMX also produce dimple membranes.

Many of these companies also manufacture dimple membranes with a bonded geotextile face for more demanding applications. Examples include American Wick Drain’s Amerdrain, Tremco’s TremDrain, Cosella’s Delta Drain, and similar products from Mar-Flex and Cetco.

“In this case, the dimples face out towards the soil, and the geotextile creates a free cavity for the water to drain down,” explains Dave Gallagher, a marketing representative at Cosella Dorken company.

EnkaDrain, by Colbond performs similarly, but has a different design. Instead of dimples, EnkaDrain relies on a tangle of polypropylene filaments to create the air gap. EnkaDrain is made from 40% to 50% post-industrial recycled content, and is available with a geotextile bonded to one or both faces.

AmerDrain 500, from American Wick Drain, claims to be the “most common product used for basement and foundations for commercial projects,” and is typical of this type of product. The sheet drain is placed next to foundation or retaining wall, protecting it from damage caused by back-filling. The geotextile faces out, keeping soil from clogging the dimples and creating a void to drain water to the footing.

Aimed primarily at below-grade commercial construction, these are becoming more common in residential markets as homes get bigger and owners build on sites with more difficult drainage issues.

Most of these dimple/geotextile products have a compressive strength of 10,000 to 15,000 psf and can drain 15 to 20 gallons per minute per lineal foot. Exact specifications for a specific product are usually posted on the manufacturer website.

Another choice for drainage boards is to use rigid or semi-rigid insulating panels. These have the same advantages over traditional aggregate drains as sheet goods: lighter weight; protection of the waterproofing membrane during backfilling operations; and better, faster drainage rates.

In addition, these panels also insulate the below grade living space. R-Values are typically about R-5 per inch. Besides the obvious energy savings and improved interior comfort, the panels reduce the risk of mold and condensation on cold basement walls.

Panels like Drain & Dry by Mar-Flex, or Tuff-N-Dri by Tremco are made from fiberglass and resin. Others are made from expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam, flexible closed-cell foam, and even mineral wool. Panels are usually available with a geotextile face on one side.

Footing Drains

Regardless of what type of drainage board you use, once the water reaches the bottom of the foundation wall a footing drain—sometimes called drain tile—must be installed to move the water away from the structure.

“Ideally, the drain tile should be installed at the top of the footing,” says Steve Gross, director of marketing at CertainTeed. “You want to intercept the water before it gets to the cold joint between the foundation wall and the footing. That’s typically a weak area for water penetration, and it’s where hydrostatic pressure is the greatest.”

For the last 50 years or so, the most common footing drain has been a perforated PVC pipe, buried beneath a few feet of washed, one-inch diameter gravel. The gravel is topped by some sort of filter that lets water pass through while keeping soil out. Historically, this was done with a layer of straw. Today, geotextile filter fabrics are used.

Some claim this solution is still the best. “We are big proponents of having the gravel down there,” says Gallagher at Cosella-Dorken. “We see some very real and significant benefits of using gravel.”

Trang Schwartz, marketing manager at American Wick Drain, says pipe-and-gravel systems work well, but are limited when high-flow drainage boards are nearing capacity. “Perforated pipe and gravel is a good system, and it moves water great, but it’s typically perforated on only 5% of its surface area,” she says. “What we offer is a product that makes it easier for water to get into that open space and move away from the structure.”

American Wick’s Akwadrain uses dimple membrane technology to create a strip drain with 65% open space, opposed to the 5% open space in perforated pipe. It has deeper dimples and a geotextile wrap to prevent clogging. The product is set against the exterior of the footing, then backfilled with gravel to bridge the gap between the sheet drain and the strip drain. The six-inch high product can handle 21 gallons per lineal foot per minute. Under hydrostatic pressure, the 12” product can handle 100 gallons a minute.

Similar products are available from Mar-Flex and Tremco.

American Wick Drain and Tremco Barrier Solutions each offer their dimpled sheet drain and drainage tile in single product to make installation easier.

Perhaps the quickest way to install a footing drain is to use Form-A-Drain from CertainTeed.

“This is a 3-in-1 solution to the most common problems contractors are dealing with,” says Gross.

Form-A-Drain is a rectangular lineal product made from PVC. Available in four full dimensional sizes—4”, 6”, 8” and 10” tall—the perforated product is used to form the footings, then left in place to collect and drain groundwater.

“First of all, there are the tremendous labor savings you get by leaving the lineals in place and not having to come back and strip wood forms,” says Gross. “Second, they are at the perfect location, perfectly level, and they’re hard-connected to a sump pit.”

Gross recommends using Form-A-Drain on both sides of the footing, which leads not only to a more level footing but also prevents groundwater—and harmful gases (when connected to a discharge system)—from accumulating under the floor.

Boccia Bros. markets a Hollow Kick Molding specifically designed for draining the interior side of the footing and under the basement slab.

Whatever system you use, Tim Carter at askthebuilder.com recommends installing the footing drains immediately after the footing is poured.

“There are advantages to doing the job this way,” he writes. “First, the space between the side of the footer and the wall can fill with collapsed dirt and/or concrete overflow from pouring the foundation wall. This stuff is tough to dig out and remove once the basement walls are poured. Besides, it is tough to work in the narrow area left along the foundation after the walls are up and poured.”

Water Disposal

So where does the water collected by footing drains go? If you’re building on a sloped lot, it’s easy. The drains connect to a pipe that runs slightly downhill or even level from the footer until it emerges from the ground.

If the lot is flat, you’ll need a sump pump. The pipe between the drain tile and the sump will run through or under your footer, so it may be easiest to install this before the footer is poured. The water that collects in the sump is then disposed of, pumped either to a French drain placed well away from the house or into a storm water drainage system. If connected to the stormwater drainage system, be sure to install backflow preventers.

Sump pumps are usually hardwired into a home’s electrical system, and may have a battery backup. Others, such as the TripleSafe Sump Pump, have a secondary backup pump in case the primary pump fails or becomes overloaded. Both pumps are hardwired into the home’s electrical system. A third pump is battery-operated in case of power failure.

Another recommended component is a water alarm. Placed inside the sump, it will emit a shrill beep if too much water accumulates in the sump.

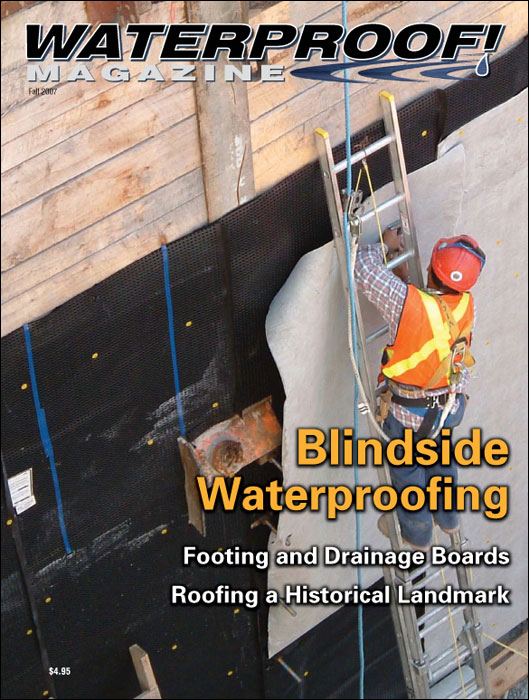

Fall 2007 Back Issue

$4.95

This is the Very first issue of WATERPROOF! Magazine.

Blindside Waterproofing

Project Profile: Roofing a Historical Landmark

Footing and Drainage Boards

AVAILABLE AS A PDF DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

This is the Very first issue of WATERPROOF! Magazine.

Blindside Waterproofing

Occasionally, waterproofing and drainage membranes have to be applied before the below-grade structural wall is built. Here are the products and techniques the experts use.

Project Profile: Roofing a Historical Landmark

The 140-year-old Salt Lake Tabernacle needed a new roof. The challenge was that it is one of the most complex—and famous—roofs in the country. Having the congested jobsite right in the middle of Utah’s most visited tourist attraction added another degree of complexity.

Footing and Drainage Boards

The key to ensuring a good, waterproof basement depends as much on the drainage system as the waterproofing membrane itself. Drainage boards relieve hydrostatic pressure by directing water to the base of the structure. Footing drains remove that water away from the building.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | PDF Downloadable Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|