By Dan Calabrese

The key to long-lasting water-resistance is to install a roof that limits movement and maintains its elasticity.

You know what it’s like when you’re old and reliable. People are always trying to find something better, even while they take you for granted and keep coming back to you when they need something they can count on.

Built-Up Roofing (BUR) systems are used to it. People have been doing it to them for more than 160 years.

For a flat roof that achieves waterproofing and drainage excellence, it’s hard to beat a multilayered system whose cornerstones are among the most water-resistant combinations known to man – asphalt and coal tar.

So why does it get such fleeting respect?

“We’re seeing built-up go to sleep for a little bit, waiting for the next big failure,” said Mike Brigham, founder of Mount Ranier, Maryland-based Built-Up Roofing Systems. “It has a history of going away for awhile and then coming back. People who believe in it strongly – school systems, municipalities – believe in hot, rubberized asphalt.”

BUR dates back to the 1840s, when it was known as composition roofing. The concept was so basic and viable that it rose to capture more than 90 percent of the flat-roofing market by the 1960s. But the emergence of other systems, along with a decline in workmanship among BUR practitioners, saw the method’s market share decline in the 1970s to as low as 40 percent.

The key to BUR’s strength and durability lies in the fact that all plies of the roof are fused together into a single, monolithic barrier that applies to the entire surface.

That eliminates numerous problems inherent to other systems, including:

- No need for fasteners, which create additional risk of leakage.

- No need for ballast, which is often laid loose in the form of stones and can be blown off by heavy winds.

- Less movement in the form of expansion and contraction, which leads to buckling, ridges and splits.

Roofing elongation does not create an alarming risk of leakage so long as the roof maintains its elasticity. The problem arises, however, as roofs age and become more likely to pull away from themselves during expansion.

The key to long-lasting water-resistance is to install a roof that limits movement and maintains its elasticity.

The idea of a BUR system is to attack the problem on both ends. First, BUR systems are designed to limit movement with high tensile strength well beyond recommended industry standards of 200 pounds per square inch. Second, the blending of all materials in a monolithic compound preserves elasticity far longer than single-ply roofs. At the same time, single-ply membranes essentially offer just one shot to stop a leak. If the membrane is compromised, water will get through.

When roofing contractors install a BUR system, they fuse the multiple plies together with hot-mopped asphalt, resulting in a compound that self-adheres completely to the roof at all points.

The natural water-resistance of asphalt only adds to the BUR’s system effectiveness as a waterproofing strategy – estimated at five times the water-resistance of a typical single-ply system.

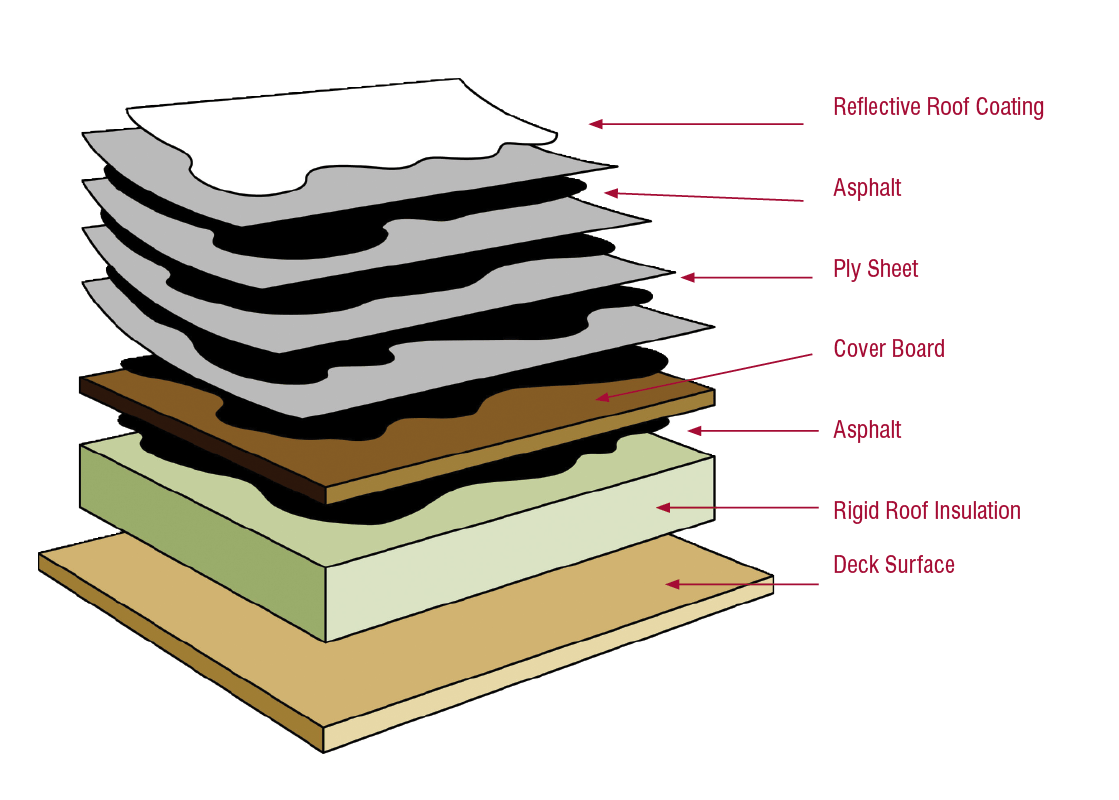

Basic installation of a BUR system involves the following steps:

- Base sheets are mechanically fastened, generally nailed, to the deck or substrate.

- Felts are installed with either hot asphalt or coal tar. You can also use a cold-applied liquid adhesive, sometimes known as solvent-based asphalt or cutback asphalt.

- Application of hot asphalt runs at 20 to 25 pounds of coal tar per 100 square feet between each ply, or three-to-five gallons of cold-applied adhesive per square.

- For the surfacing, install a cap sheet with the same amount of bitumen or lap cement as is used to install the plies. Then apply a flood coat of roughly 60 pounds per square of asphalt or 70 pounds per square of coal tar. Then embed 400-to-500 pounds per square of gravel, or 300 to 400 pounds per square of slag.

For emulsion surfacing, use about three gallons per square and apply an aluminum reflective coating after the emulsion cures to reflect UV rays.

You can install a BUR on just about any type of roof deck, but you don’t always do it the same way. You need to know some basic differences for application with different types of decks, including:

- You can’t mop a BUR system to a wood roof deck without putting down a rosin sheet and base sheet.

- Steel roof decks need a thickness of 22-gauge, minimum, along with some approved insulation, which should be mechanically attached to the deck to provide a substrate.

- Before you mop felts directly to polyisocyanurate insulation, be sure the manufacturer will still warranty the roof. You might need a coverboard, such as wood fiber or perlite, in order to preserve the warranty. The same goes for the use of adhesives to attach insulation. Check with manufacturers first.

- The BUR system is often mopped directly to structural concrete roof decks – after the deck is cleaned – although you can use mechanically attached thermal insulation as a substrate. But with lightweight insulating concrete, as well as pre-cast gypsum panels or poured gypsum, you’ll need to attach venting base sheets with fasteners, after which you might install insulation in between the base sheet and the roof membrane.

- Cement fiber roof decks will definitely need a base sheet or insulation mechanically attached.

As a general rule of thumb, a BUR roof lasts longer if it has more plies – although that is obviously impacted by outside factors such as climate, foot traffic, materials used, workmanship and roof slope.

Efficient drainage is crucial to the overall effectiveness of your BUR system. The design of the deck and roof substrate must drain to enough outlets – situated in the right spots – to remove water such that it can never pond longer than 24 hours.

Many roofing systems are designed with integral drainage channels, but contact between the membrane and the insulation can impede water flow. Installers should take care to ensure that the finished roof membrane has sufficient slope to minimize the amount of water retained after rain.

Steve James of St. Petersburg-based Florida Southern Roofing said this old system is regaining momentum partly because of improved materials, particularly fiberglass felt.

“The biggest improvement of late has been the fiberglass felt as opposed to rag felt,” James said. “This goes back a few years, but combined with proper practice and old-school workmanship, you get what you get with a built-up roof – a good many years of service with a reasonable price tag.”

Brigham says roofers are taking a heightened interest in new roofing materials – not only fiberglass felt but a variety of hybrids and other new options. He worries, however, that they are not always doing so for the right reasons.

“Architects, it seems, over the years have lost sight of what they’re really buying,” Brigham said. “Now some of them are buying a warranty instead of a roofing system.”

The proven nature of BUR systems, combined with the constant quest for new concepts, is creating new market opportunities for those ready to seize them.

Carlisle, Pennsylvania-based Carlisle SynTec offers a variation on the BUR that it calls FleeceBACK. The product was introduced 13 years ago.

It features multiple membranes and is promoted as having outstanding UV- and ozone-weathering ability, as well as an ability to last 50 years without dropping below 200% elongation.

“Built-up roofing has been around a long time, and you have building owners out there who may have had a satisfactory experience with them, so they’re interested in going back to that multi-layer approach,” said Ron Goodman, FleeceBACK product manager for Carlisle SynTec.

“That would be one market driver. Another one we run into is compatibility with existing asphalt roofs. Building owners are looking to conserve costs and extend the life of the existing roof. Either they have an existing

smooth built-up roof, where we can go in and put on an EPM or TPO cap sheet that’s hot-mopped to the smooth built-up roof.”

One variable among BUR systems usually depends on geography. BUR systems in the south most likely include a white-reflective roof – which fends off UV rays and reduces air conditioning usage in the building. BUR systems in the northern U.S., by contrast, are more likely to be dark colored so as to help retain heat.

The currently heightened interest in energy-efficiency is helping to drive this trend, particularly builders’ interest in seeing their buildings certified under

the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Program.

On the surface, you might say, BUR systems seem relatively foolproof, which is probably why the concept has remained in use for the better part of two centuries.

But the success of any particular installation always depends on the right materials, the best workmanship and a sound design. As more roofers master these techniques, BUR systems improve their chances of being around a century from now.

Summer 2018 Back Issue

$4.95

Livable Basements

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|