by Dan Calabrese

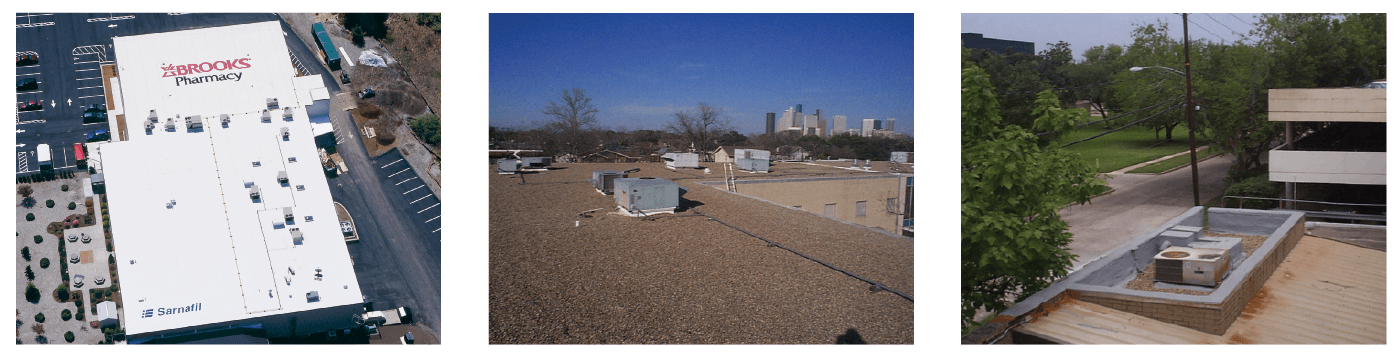

Contractors say it’s crucial to get a slope of at least a quarter-inch per foot in a flat roof.

If someone calls you and tells you their flat roof is leaking, where do you go and look?

Not on the roof. At least that’s not where Byron Degem looks. To understand why, think gravity.

“I don’t go on the roof,” said Degem, president of Houston-based Commercial and Industrial Applicators Inc. “I look at the ceiling and see where it’s heading.”

Getting a flat roof to perform seems fairly simple, and theoretically it is. Water goes where you give it an outlet, especially when the outlet is downward. So you seal up openings and build enough of a slope that the outlet you create is downward and away.

Problem solved.

Quality Counts

But it’s never quite so easy, is it? Flat roof contractors interviewed for this story said the challenge inherent in getting flat roofs to perform usually comes down to workmanship. The issue is not so much knowing how to do it, but rather putting in the time, effort and money to do it right.

“Poor installation is what we chase around here,” said Steve James, of Bradenton, Florida-based Southern Florida Roofing. “For every good, reputable roofer around here, it seems like there’s a couple dozen out there doing inferior work. If you’re following manufacturers’ recommendations, roofs do their thing. A low slope will do it. It comes down to workmanship, because manufacturers pay a lot of people to iron out the bugs and deficiencies.”

Contractors say it’s crucial to get a slope of at least a quarter-inch per foot in a flat roof, although they acknowledge with some frustration that many roofers past and present have thought otherwise. As a result, slope-free roofs pond and become breeding grounds for mosquitoes, mold and other less-than-desirable substances.

But ponding water isn’t only a problem for what it attracts. At 5.5 pounds per square foot per inch, water is heavy. Let a square inch of water pond across a 400-square-foot roof, and you’ve got a ton of weight on top of your building.

“Most manufacturers require that, for the warranty on their products to be valid, that water be drained or pitched so the roofs don’t pond the water,” said Jerry Barnett, president of Canton, Michigan-based Barnett Roofing and Siding Inc. “Some of the lesser companies will use a torch-down roof over the insulation, which creates more of a water pocket. That gives the industry a bad name.”

Those who find themselves with a flat roof with no slope, and ponding or leaking developing, should try to build some slope into the roof it it’s structurally possible. But it may not be possible, in which case contractors recommend putting in a roof drain and stripping in all the seams.

But depending how serious the problem is, that could be just the start.

“The economy is not so great, and sometimes the economics doesn’t allow you to do it correctly, so they take a chance on doing a less quality job,” Barnett said. “When it starts leaking so badly that there’s no longer anything that can be done to solve the problem, they have to go back and tear everything back down to the deck, and put the roof on the way it should have been.”

Completely replacing such a roof can require contractors to remove the old roof system down to the structural deck, then replace bad decking and install wood blocking at the perimeter.

The wood blocking should be equal to the thickness of insulation on three sides, and a little less at the drip edge to allow for better drainage.

Next comes thermal insulation, a cover board, foam and roof board – followed by roof deck screws and plates.

Finally, a fully adhered, liquid rubber membrane provides a crucial layer of protection without seams or overlap.

According to James, poor handling of flashing can quickly lead to trouble.

“Not nailing a flashing off at the top is one of a million things I can mention as far as cutting corners,” James said. “Instead of using the right tools for flashing roof drains properly, whatever they’ve got on the truck they’ll do the job with.”

Degem said flashing is often handled by poorly paid employees, who are nevertheless expected to ace a very challenging task.

Elastomeric Roofing

For Degem, the very presence of seams is an unacceptable leak risk, which is why he specializes in a spray-on system he calls Elastomeric roofing.

Essentially, the system involves the application of a fully adhered, 1,000- to 2,000-milimeter-thick, breathable, self-drying, waterproof membrane.

“It’s a highly detailed application,” Degem said. “All-membrane roofs don’t flash themselves. They have to have a metal counterflashing to make sure it runs over the metal and down onto the roof.”

Degem touts the system as incapable of leaking because the material is impermeable and the application involves no seams, flashing or overlaps.

“It’s a very thick, low-maintenance, trouble-free roof,” Degem said. “I had a survey where I asked people to choose between a roof system that came in rolls 36 inches wide and 50 feet long, and you overlapped them and had miles and miles of seams on the roof, or if you had one that was 100 percent seamless. What would you have? They chose 100 percent seamless. And if you could have one that was fully adhered or ballasted, what would you pick? Fully adhered.”

The thicker membrane, compared to alternatives that can be as thin as 50 milimeters, often seal the deal. He can also install it over an existing roof, which eliminates the cost, time and mid-installation leak risk associated with roof replacement. And while Degem’s company has developed a solid reputation from having applied the systems for nearly 30 years, he said it was difficult to get acceptance in the marketplace at first.

“When I first started doing sales calls when I got into the industry, they said if I could show them a roof that had been installed 10 years and working well, they would consider it,” Degem said.

Tim Carter, owner of the AsktheBuilder.com web site and a long-time contractor, is a strong advocate of synthetic membranes as an alternative to mopped asphalt.

“Asphalt is simply old technology and is prone to failure,” Carter said. “The system is dependent upon expert workmanship for long-term high performance. Excellent workmanship is harder and harder to find these days.”

Carter also touts the superior manufacturers’ backing of membrane materials.

“You will be surprised at the warranties you can get with the membrane materials,” Carter said. “When you sit down and analyze the cost versus the benefits, you will do well by upgrading to the membranes. So far, every membrane roof I have installed has been leak-free. Some have been on for more than 12 years. If I had a low slope on my own house, I can tell you that I would put an EPDM or CSPE membrane on it so fast your head would spin.”

EPDM is a synthetic rubber polymer made from ethylene and propylene monomers. A liquid version, commonly used in roofing, cures by chemical reaction at ordinary temperatures to form a flexible rubber membrane.

CSPE is a synthetic rubber, originating as a thermoplastic material, that softens when heated and hardens when cooled, allowing it to be heat-welded when installed. It is used as a single-ply roofing membrane.

Material Options

Flat roofs essentially come in the following varieties:

Built-Up Roofs. Generally the cheapest option, these are built from three or more plies of waterproof material, alternated with hot tar and ballasted by stone. The gravel in a built-up roof is an effective fire retardant, but a built-up roof is heavy and the installation can be a messy job. Smelly too. And if you do spring a leak, it can be hard to find it.

Modified Bitumen. Moderately priced, this is a single-ply, rolled system with a mineral-based wear surface. If installed via the torch-down method, it is achieved by heating the adhesive as the material is unrolled. Newer peel-and-stick systems are safer (no fire hazard) and are easy enough that many homeowners can install them in DIY fashion.

Rubber Membrane. Although this type is at the higher end of the cost spectrum, it uses durable material that resists damage from sunlight and can be attached with fasteners or glue, or ballasted with stone. The rubber is scuff-resistant and easy to patch in case of a leak.

Solving Problems

A problem for roofers and building owners is the fact that a cheap, poorly constructed roof won’t always reveal itself to be a problem immediately.

As a general rule, a flat roof will cost $250 to $350 per square foot. Whether a particular project falls on the low or high end of that spectrum will be determined by everything from the cost of labor and materials to the track record and capability of the contractor.

As with most areas of construction quality materials and quality installation will determine how long the roof lasts.

Summer 2008 Back Issue

$4.95

Midwest Flooding

Dealing with Drainage

Crack Repair for CMU Foundations

Getting Flat Roofs to Perform

AVAILABLE AS A PDF DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Midwest Flooding

By Melissa Morton

Torrential rainfall in the upper Midwest has flooded hundreds of square miles along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Waterproofers are helping out as much as they can.

Dealing with Drainage

By Dan Calabrese

Every building needs a drainage system. This involves everything from properly sloping the lot to ensuring drain tiles and sump pumps are adequate.

Crack Repair for CMU Foundations

By Clark Ricks

Concrete block, or CMU is commonly used for basement walls in much of the country. Modern materials have created new options for repairing the cracks that inevitably appear.

Getting Flat Roofs to Perform

By Dan Calabrese

Standard in commercial construction, flat roofs are also common for residential work in some regions. The key to performance is proper installation, quality materials and a slight pitch.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | PDF Downloadable Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|