by Stephen Andras CWS, CSRS

“Anyone that has installed basement drainage systems has encountered iron bacteria at one time or another.”

Throughout my 28-year career as a basement drainage system specialist, there has been a nagging problem that our industry seemed to ignore: iron bacteria.

Anyone that has installed basement drainage systems has encountered iron bacteria at one time or another. I remember back in my early years being called in as an expert witness to testify about a drainage system being clogged with a slimy orange substance. After the homeowner’s lawyer showed the jury these awful looking pictures of iron bacteria (back then we called it the “red stuff” ), I watched the basement contractor on the stand squirm a little and say, “I’ve never seen this before” and “this is a rare situation”.

This has been the problem all along in our industry. Yet all of us—including myself until a few years ago—refused to admit there is a problem. Most basement drainage systems come with a warranty from 20 years to Life-of-Structure. Read those warranties, though, and one will find that most, if not all, exclude iron ocher, iron bacteria, iron algae or whatever someone decides to call it.

I, for one, want to go on record that for 26 years, I did not have a clue about this “rare problem,” except that the longer I was in business, the more it seemed I was running into it. I guess I can explain it this way: when you do 100 jobs a year, you will not run into it as much as when you are doing 2500 jobs a year.

Two years ago, I started on a mission to help customers in my area with this problem. I visited jobsites, collected samples, talked to experts in many fields, and researched every article I could from around the world via the internet. I contacted contractors from around the US and Canada, asking questions to determine how widespread iron bacteria was in their area. I asked consumers with the problem to contact me.

This problem was more prevalent in some areas than others. But it wasn`t as rare as everyone was saying. The biggest problem I see about iron bacteria is that our industry hasn’t even admitted that we have a problem. They will admit it is a “rare problem” but by doing so, they can exclude it as a problem that needs to be addressed. It is not so rare for the homeowner who has to deal with the problem.

I feel it is my duty to the industry to declare that we need to deal with iron bacteria if we truly care about our customers.

First let me explain what iron bacteria is. Then I want to discuss what can be done to help deal with it.

Many of us never took the time to find out what we were even dealing with. I believe this is not because we didn’t care about our customers, but rather we didn’t have the time because we were all too busy out in the field helping people.

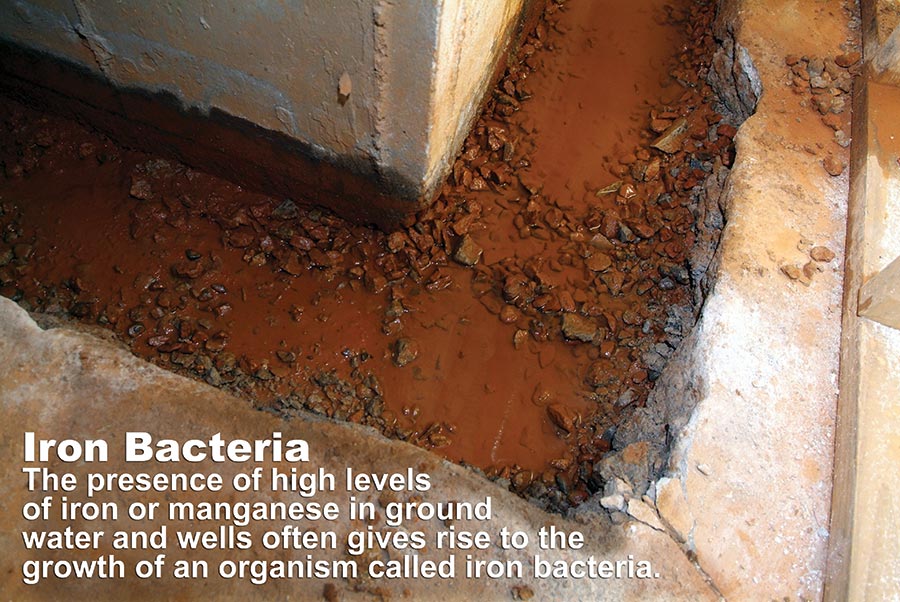

So why do I call it an iron bacteria problem rather than an iron ocher or iron algae problem? Iron ocher is not the problem. Rather, it’s a mineral that iron bacteria feeds on. Iron bacteria are living microorganisms. Two types of iron bacteria have the ability to attach themselves to the side of a pump, pipe, or even crushed stone. These iron bacteria do this to feed on the nutrients flowing by in the water. Once they are established other iron bacteria have the ability to attach themselves to the first bacteria, starting a colony and forming a plaque-like biofilm on the drainage system components.

This was a breakthrough for me. Finally, I understood at least what I was dealing with: a live colony of microorganisms that fed on nutrients in the groundwater within the drainage system. Iron bacteria use this food source (iron ocher) like humans use oxygen.

These live microorganisms are not known to be harmful to humans. However, they are a nuisance and can clog any drainage system. And some of the ways that homeowners and contractors deal with iron bacteria may be harmful to the environment. Chemical formulas like ‘Iron Out” will help rid the iron bacteria from the drainage system, but if they are pumped out into the yard near a stream, pond, etc. they will kill aquatic plant and pond life.

My research has proven that hot water at about 140 degrees will easily clean and remove these iron bacteria colonies. In effect, by flushing a drainage system with 140 degree water, one is pasteurizing the bacteria. My company has purchased and customized an on-demand hot water pressure washer. You don’t need much pressure; somewhere around 300 psi is fine.

We originally tested our theory by using a customer’s hot water tank, but found out we needed way more than 35 or 40 gallons. The hot water unit is great because it can roll right up to the bulkhead or basement entrance. We will hook up a cold water hose to an outside faucet and then turn on the diesel-fired burner. The unit has a 100-foot hose and special nozzles to “hot flush” the drainage system. This is the safest and most earth-friendly way of dealing with iron bacteria.

That doesn’t solve the problem, though. After looking at all the drainage systems available today, I discovered the majority of them did not have access ports for a contractor to be able to flush them. The few manufacturers that had a “port” for their system really was more of a marketing ploy to impress a homeowner or contractor, but not very effective in real life.

This brings me to another point that is very important. I believe that when a contractor breaks open a basement floor to install a drainage system, the iron bacteria problem might be a very small one, but because he is introducing air (and carbon dioxide which iron bacteria thrive on), he is causing it to flourish even more.

This brings me to another important point: With all that people do in their basements nowadays, and with what we know about radon, ground moisture, humidity, bugs and now iron bacteria, why are we still installing open channel systems?

I admit I installed many open systems in the past, but now that people utilize their basements more than ever, I have come to believe that open-backed drainage systems are not the right thing to do. In fact, my company no longer even offers an open drainage system.

This should cause all basement contractors to ask themselves some serious questions. Why is our industry encapsulating crawl spaces, yet we are still venting the ground under the basement slab by installing an open channel around the whole basement? Why are we concerned with installing air- tight sump liners yet have a chimney installed around the perimeter of the basement slab? Why be concerned with an airtight floor drain or sump liner but install an open trench drain across the bulkhead stairs? Why do we install an open channel around the perimeter of the basement thereby letting ground humidity up into the basement environment and then when our customers say they have more humidity, we tell them to run a dehumidifier? When the dehumidifier removes all the moisture from within the basement it will draw moisture up from that open channel. Why are we doing these things?

As an industry we need to change the way we think and install our systems accordingly.

I estimate that in the Northeast one out of five basements have some amount of iron bacteria. Other parts of the country are also affected. When we as an industry tell our customers that a problem is rare and limit our liability by stating that our warranties do not cover iron bacteria, we are part of the problem, not part of the solution.

My advice to all of you is to strive to solve 100% of your customer’s basement problems even if it seems rare to you.

There is one last thing I want to mention. Like any industry, when we are faced with changes that we need to make, there will always be individuals and manufacturers that will resist change because it will cut into their profits or that their product will be leapfrogged by technology.

To all of you, my fellow contractors, manufacturers and friends, I encourage you to embrace the future with open arms and always be willing to change the way you do things if it will better your customer’s quality of life. n

Stephen Andras is the president of Pioneer Basement Systems in Westport, Mass., and has more than 30 years experience in the waterproofing industry. Reprinted with permission of NAWSRC.

Thank you for helping me understand the issues I am faced in my basement and what is helpful, and what is not. There is not a lot of candor on this subject. I’d rather hear a painful truth than dealt a bunch of hogwash.

Hello, I own a basement waterproofing company here in Michigan and I stumbled across this page trying to research the best way to help a customer with his iron bacteria problem. He currently has a drainage system installed in his basement and I don’t want to sell taking out the existing system and putting a new system in with some maintenance without having the correct information for him. I strongly agree that our industry needs to find answers to this problem that can help our customers to treat this problem at an affordable cost and not having to replace their drainage systems every couple years. Any information that you have found would be helpful to know. I appreciate you as someone in our line of work also seeing the problem and wanting to find answers for our customers. We have came across this problem only a few times in the 12 years we have been in business but have been encountering it more and I would love to be able to tell my customers the proper way of fixing the problem and being able to stand by our work.

I’m in Michigan and had my basement “waterproofed ” with a lifetime warranty in 2002. It’s been wet ever since. I called them out once and the original owners put some landscape fabric around some of the pvc tile theput in, but there is now a lot of this iron ochre and sand in the drain system. I wash it out two or three times a year, but the floor is always wet up against the walls. They said to pour iron out down between the wall and the plastic they put up. I’m 70 years old and very arthritic. It’s really hard just to flush out the thing. They won’t do anything else without charging me a bunch of more money.

Do you have any suggestions?

This is really a great article. I myself have been dealing with this issue for about 10 years. We bought our house in summer of 2012, in the suburbs of Milwaukee, WI. In December of that same year, we had a lot of heavy snow, and then warm weather that melted it all. It was a shock that first that I saw water pouring up between the wall and the slab.

Since then I have educated myself on what was happening in the basement. I have had so many drain tile companies to look at the issue. Not one of them fully understood what was happening. One of them even said he’d never seen such a thing and wouldn’t even quote the job. This shows that the author of this article is correct and changes need to be made in the industry.

For those having issues, I can tell you what works for me. I have Iron Ochre, and I have been dry for years. If you have cleanouts in your drain system, look inside them. Part of my problem is the people who owned the house had someone do the drain tile, but didn’t pitch it properly. Water is able to sit idle, and the bacteria flourish in that environment.

If you have the black corrugated pipe in your system, you may want to consider having it replaced with something smooth. The weep holes of that system are in the “valleys” of the corrugation. The bacteria are able to latch onto these places. As water is running through the pipe, it gives them a place to hang onto where the water doesn’t wash them away

I purchased a power washer, and a sewer jetter hose to attach to it. I run it through my system twice a year. The power washer was a couple hundred dollars ( i bought an electric one so I could use it in my basement, although a gas powered one would be more powerful) and the jetter hose was like one hundred dollars. The one I got was from ClogHog, and works well. The have hoses and adapters for most if not all power washers.

If you have Iron Ochre, and are planning on redoing your drain tile, get smooth pipe for the drain, with a cleanout at every corner so you can flush the system periodically.