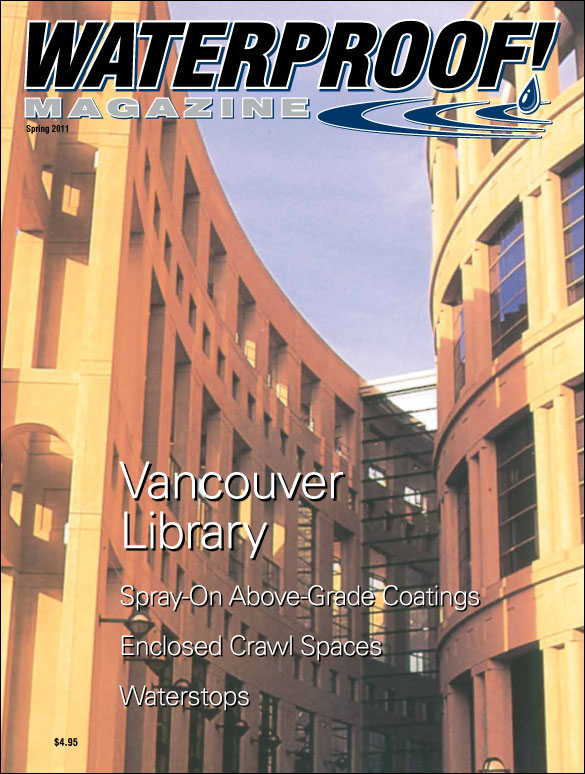

Among the most iconic buildings in downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, is the nine-story Vancouver Public Library (VPL) Central Branch.

The library—an otherwise ordinary rectangular box—is surrounded by a free-standing, elliptical, colonnaded wall that some observers have compared to Rome’s Coliseum. Built for more than just aesthetics, the curved walls feature reading and study nooks, that are accessed by skywalks connected to the central building.

Inside the building, another set of elliptical walls create an enormous glass-enclosed concourse. The floor-to-ceiling windows offer natural light and an outstanding view of the surrounding city.

To relieve congestion on the street, a 700-stall public parking area was built below-grade.

To relieve congestion on the street, a 700-stall public parking area was built below-grade.

As might be expected for a Pacific Northwest climate, Vancouver receives more than 60 inches of precipitation per year, so waterproofing the structure was a major concern. The city also prides itself on being a leader in the green construction movement, so the waterproofing system had to be “green” as well as foolproof.

To handle both of these concerns, designers used Kryton’s Hydrostop Sealer, an integral waterproofing, during the initial construction. It’s a clear, water-based sprayable sealer with silane and siloxane compounds to repel water from concrete, brick, mortar and masonry.

Perhaps the building’s most impressive feature, though, is its green roof. At 33,000 sq. ft., the growing medium is as big as a football field. It was designed by one of the world’s most renown landscape architects, 86-year-old Cornelia Oberlander.

Chuck Cronenweth, western regional manager for American Hydrotech, was brought in when the project was still in the design phase to help resolve some of the technical difficulties presented by a green roof of this size.

Because Oberlander envisioned an “intensive” roof with soil depths exceeding 12 inches, it was important to keep the weight of the waterproofing and drainage components to a minimum.

First, the roof deck was sealed with a waterproofing membrane. Designers chose a seamless, fluid-applied, rubberized asphalt product supplied by American Hydrotech. For drainage, builders used a geonet composite with an nonwoven geotextile instead of the traditional gravel. This choice reduced roof loads and was far easier to transport to the top of the nine-story structure.

The 42,000 plants on the greenroof were planted by hand, and required artificial irrigation for the first few months. In place for more than a decade now, they’re virtually maintenance free, except for an annual raking to remove dead growth.

The lightweight growing medium was craned onto the roof in giant buckets, and installed to a depth of 14 inches. Composed of 1/3 sand, 1/3 pumice and 1/3 humus it weighs no more than 76 lbs. per cu ft. when saturated. Because of the busy downtown location, this work could only be done between 3 pm and 11 pm.

Contractors also installed an irrigation system to help the 42,000 transplanted grasses and other plants become established. In subsequent years the irrigation system has only been used in periods of extreme drought.

The thousands of plants were arranged in sweeping curves to mimic the Fraser River that flows through the area. Sixteen maple trees are planted on an adjoining terrace. When seen from the 21-story Federal Tower, part of the library complex, and other high rises surrounding the library, the shapes suggest movement of water in an otherwise static environment.

But the roof provides more than just aesthetic benefits. With fourteen inches of growing medium, the roof provides excellent insulation for the building from the cold as well as heat, resulting in energy cost savings. And while not a primary design consideration, the green roof protects the roof membrane from climatic extremes and physical abuse, greatly increasing the life expectancy of the roof.

The 42,000 plants on the greenroof were planted by hand, and required artificial irrigation for the first few months. In place for more than a decade now, they’re virtually maintenance free, except for an annual raking to remove dead growth.

In 2004, a one-year study to monitor stormwater was completed. It showed a 48% reduction in runoff volume. More importantly, the green roof reduced peak flows most during summer storm events.

The greenroof was originally designed to be accessible to the public, but architects were asked to add two additional stories to the original design for use as office space, which renders the roof inaccessible. Since the roof is considered inaccessible, there are no guard rails or parapets to prevent a nine-story fall over the edge.

Recently though, the city has been rethinking that decision and is studying ways to make the roof open to the public. Brian Hutchinson, a columnist for Canada’s National Post, visited the roof last year as part of his story on improving public access.

He reports, “The visual effect is profound, almost discombobulating. A field of tall grass, planted in two colors, gives way to low ground cover. The river pattern is obvious and appears to run forever, even as the roof abruptly ends. The landscape is flat but somehow seems to gently rise and fall. Japanese maples, planted one story below along a forgotten outdoor plaza, push upwards, toward the roof, adding another layer of depth. It is quiet. Up here, the city seems at peace.”

Project Profile

FAST FACTS

- Project Name: Library Square

- Location: Vancouver, B.C., Canada

- Size: 398,000 sq. ft.

- Cost: $107 million

- Year Completed: 1995

CONSTRUCTION TEAM

Landscape Architect: Cornelia Oberlander, FASLA, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Landscape Architects

Architect: Moshe Safdie, Moshe Safdie and Associates; Downs Archambault and Partners

General Contractor: PCL Constructors Pacific Ltd.

Greenroof System: American Hydrotech

Spring 2011 Back Issue

$4.95

Waterstops, How and Why

Project Profile: Vancouver Library

New Data on Enclosed Crawlspaces

Spray-on Coatings for Above-Grade Work

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Waterstops, How and Why:

Long used for heavy commercial work—especially in tunnels and retention ponds—waterstops are becoming more common for waterproofing light commercial jobs as well.

Project Profile: Vancouver Library

As innovative as it is green, this project showcases a wide array of new waterproofing technologies, from the integral waterproofing in the foundation to the green roof fifty feet above grade.

New Data on Enclosed Crawlspaces

As energy efficiency has become a top priority for homebuilders, enclosed crawlspaces are becoming more common. But the contractor must be careful to avoid the condensation and mold issues that can become problematic in poor quality installations.

Spray-on Coatings for Above-Grade Work

Recent developments in spray-applied coatings make them a top choice for above grade work. Compare the advantages, and find the product that’s best for your next job.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|