Concrete slabs are not impervious to water. In fact, given the right environmental conditions, the floor slab can transmit gallons of water into the living space as vapor, and in extreme cases, actually show ponding water.

“High moisture levels can contribute to unhealthy air, mold, and even structural problems,” says Ken Huggins, president of Basement Rescue. “Even if you’re not living there and it’s just storage, that moisture can ruin floors, rugs, wooden flooring and the items being stored. There are also health issues and odors to deal with.”

So, how does one fix a floor with a vapor transmission problem? The pre-construction solution is to use an underslab vapor barrier. (See The Underslab Solution in the Winter 2009 issue online). These heavy plastic sheets effectively prevent moisture and other gasses from penetrating the slab.

Unfortunately, residential and older commercial buildings usually do not have an underslab barrier. Or the barrier could be so torn and damaged that it is no longer effective. The good news is that innovative retrofit solutions exist which don’t require removing the slab.

Pinpointing the Source

The first step to determine if an underslab moisture barrier is needed is to verify that moisture is actually coming through the slab.

Ken Cotten, owner of Waterproof.com, says up to 90% of the moisture problems he deals with are wall-related. “Floor moisture is a rarity,” he says, “but it does happen.”

Joe Boccia, owner of Boccia, Inc., reports that in New England it’s much more common. Up to 50% of his calls require some sort of floor treatment.

A few years ago, Köster, a worldwide leader in waterproofing solutions, conducted a survey to pinpoint basement moisture sources. They found that 82% of cases had moisture only on the walls. A scant 4% had moisture on the floor only. The remaining 13% had problems with both the walls and the floor. Of the cases with moisture issues on the floor, about half had moisture seeping through cracks; the others had moisture in larger areas.

Be sure to eliminate the possibility that the moisture is coming from interior sources. Huggins says that he’s seen basements with obviously damp floors, but the slab was impervious. The problem was literally in the air.

“Just like a cold drink will form water droplets on the outside of the glass,” he says, “if you have a cold concrete floor and it’s a really humid climate, you’ll get a considerable amount condensation on the floors and walls.”

Besides slabs, Boccia says that common sources of humidity are unvented showers, disconnected dryer vents, and open windows.

Is a Barrier Needed?

The best way to determine if a moisture barrier is needed is to tape a sheet of plastic (covering at least several square feet) to the floor. After 24 hours or more, peel back the plastic and see if there are signs of condensation. Water on the bottom of the sheet means moisture is coming through the slab. If droplets form on the top of the plastic sheet, the problem is likely caused by excessive indoor humidity.

Be aware that moisture problems are frequently seasonal, and that a single “dry” result doesn’t rule out problems. Test again after rainstorms, spring thaws, or other event that creates soil saturation near your home.

There are other tell-tale signs of floor moisture. If the surface is painted or sealed, there might be water-filled blisters in the coating. Pop them, and they sometimes squirt water several feet into the air.

Exposed concrete sometimes shows efflorescence, a residue—usually white—of mineral salts being left behind by the migrating moisture.

Dehumidification

If tests determine that the moisture is condensation-related, a dehumidifier is often all that is needed. HQ Hometek and EZ Breathe—as well as several others—make units specifically for basement dehumidification.

Be aware that this approach requires a “breathable” floor system. There are porous carpets, paints, and other floor coverings on the market that allow moisture to pass through them. Otherwise, moisture will build up between the slab and the finish floor system.

Huggins tells of one job where the floor of an unfinished basement was literally soaking. He discovered that all of the water was condensation. “We put in a dehumidifier, and two days later the problem was gone,” he says. “But you’ve got to keep the machines running,” he continues. “If they leave on vacation and shut everything off for a few weeks, when they come back there’ll be water on the floor again.”

Erica LaCroix, at EZ Breathe, says water vapor coming through slabs accounts for up to 80% of a home’s indoor moisture. Basement humidifiers capture that moisture at it source, the ground level, keeping airborne moisture levels at acceptable levels.

“Dehumidifiers will only remove humidity from the air,” warns Boccia. “If you have an actual seep, it won’t do anything with liquid water.”

Sealants, Coatings, and Densifiers,

Some companies market sealers and coatings for the residential market—typically epoxy or urethanes—to seal off the slab. In order for these products to bond properly, the floor must be clean, dry, and free of impurities. Often, shot-blasting is used to prepare the surface.

This type of product is typically used in conjunction with footing drains. Otherwise the pressure is too extreme.

Boccia points out coating strengths don’t matter if the concrete is weak. “The coating may be tested to 25,000 psi,” he says, “but the tensile strength of the concrete is only 2,500 or 3000 psi, so the concrete will spall and the coating will fail.”

Huggins adds, “If the floor shifts, there’s nothing strong enough to hold two slabs of concrete together. So if the floor cracks, your barrier will fail.

Bryan Coulter, vice president of architectural products at Polyguard, says it’s a matter of using the right product for the circumstances.

On residential jobs though, the stakes are higher. “Once the coating is covered, it can’t be checked,” says Tom Fallon, vice-president of sales and marketing at Cosella-Doerken. ‘It’s basically ‘seal it off and hope it works.’ But you get enough hydrostatic pressure or vapor pressure under it and it will inevitably flake off.”

One class of “coating” that may work on residential jobs is the crystalline slurry coats. Made by companies such as Aquafin, Köster, Kryton, Xypex, and others, the chemicals soak into the concrete and form crystals within the voids and channels inside the surface of the concrete. This reduces permeability and porosity of the concrete, restricting the flow of fluids—but not vapors—through the matrix. Because they bond with the concrete chemically, they cannot delaminate. Depending on the job, product chosen, and installation technique, these may be a viable option.

Split Slabs

In commercial applications, the “split slab” is a common solution. Basically, the crew lays a regular underslab membrane over the existing floor, and then pours another concrete floor on top of it.

Split-slabs are sometimes used in new construction, in high-use areas where designers want to separate the “wear deck” of the concrete from the “structural deck.” These include parking garages, airport roadways, and sports facilities. As such, they have a long and successful history. Water that passes through the wear deck at cracks and cold joints is caught by the buried waterproofing membrane where it can be managed to drains.

For commercial applications, a split-slab may be the best solution. Tom Stoebner, business development manager at Raven Industries, says there are literally dozens of companies making good quality membranes for this type of work, including his own.

“The products that work well for split slabs are the same ones that work well in traditional underslab applications,” he says. “As long as the product meets ASTM 745, it’s probably more than adequate.”

For residential applications though, split slabs have drawbacks. For starters, there’s the issue of interfering walls and the hassle of getting concrete into the basement. But there’s also the issue of headspace.

“ACI doesn’t recommend that slabs be less than 3 inches thick, to ensure even curing and drying,” explains Fallon, “so that means that you’ll lose about four inches of headroom.”

The Dimple Membrane

A better way, says Fallon, is to use a dimple membrane. “You just lay the dimpled sheet down, and then put down the OSB or plywood subfloor over that,” he explains. “You’ll lose one inch of headroom instead of three or four. Any moisture that comes up from the bottom condenses on the waterproof dimple sheet and runs freely to the existing sewer drain. The occupants won’t even see it.”

He points out that dimple sheets also create a thermal break, and creates a more comfortable floor. Most importantly, it’s reliable. “It takes away the ‘if factor,’” he says.

Boccia says he sometimes uses dimple sheets, but instead of topping them with wood, pours three inches of concrete over the top. He admits that this is a “belt-and-suspenders” approach and goes far beyond what’s usually necessary.

Footing Drains

Drainage is an integral part of any waterproofing solution. Except for the dimple membrane solution above, which uses the pre-existing floor drain, all of the methods discussed in this article should be coupled with perimeter footing drains.

“Perforated pipe in gravel is the most common solution to floor moisture problems,” says Boccia. “It deals with the water no matter where it’s coming from, and removes water from under the slab before it ever comes into contact with the concrete.”

Cotten, at Waterproof.com, markets at least four different types of perimeter drains. “What we do is remove a narrow strip of the slab— about 6 inches wide—around the interior of the basement. We leave the footings in place. We remove just enough to catch the water coming under the footer.”

“These relieve a tremendous amount of pressure,” Cotten continues. “Sometimes when we puncture the slab, water literally comes spraying out.” Installers then place an inconspicuous drain channel in the trench to affect a permanent solution.

Joe Boccia, who has been installing perimeter drains for more than 35 years, stands by the perimeter drain approach. His company offers a fully-transferrable guarantee that the problem will not return for the life of the structure.

Conclusion

Whether the number of slab-related moisture problems is 50% of your calls, or only 10%, there are a number of solid, proven solutions. Whether the situation requires installing perimeter drains, a split slab, dimple membrane, dehumidifiers, or some combination, a wide range of products are available to meet your need. n

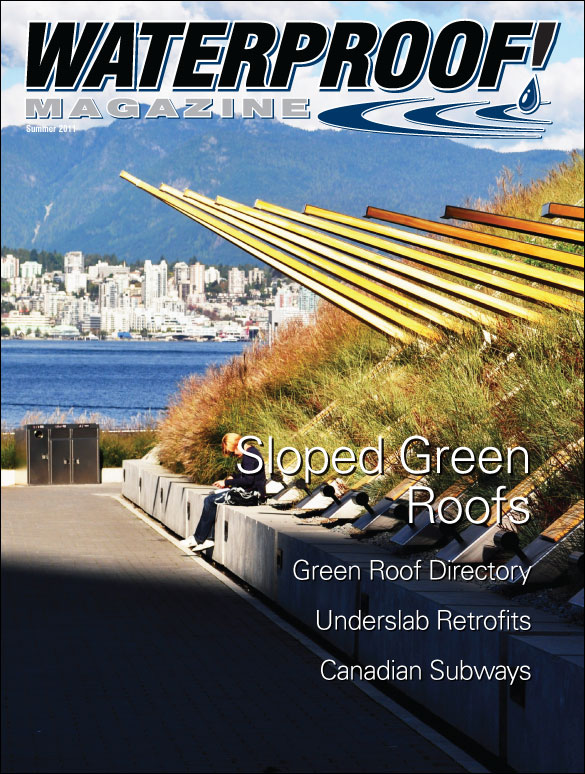

Summer 2011 Back Issue

$4.95

Underslab Retrofits

Project Profile: Canadian Subways

Sloped Green Roofs

Green Roof Directory

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Underslab Retrofits

If an underslab barrier should have been installed, but wasn’t, there are still ways to prevent moisture intrusion. Split slabs, dimple membranes, and high performance coatings are all options.

Project Profile: Canadian Subways

Two projects in Vancouver and Calgary show how waterproofing contractors tackled these massive jobs, installing more than a million square feet of material on each project.

Sloped Green Roofs

It’s possible to install energy-efficient, long-lasting vegetative roofs on even steep pitches. Soil retention and water issues can be solved with a combination of the right soils, plants, and anchoring systems.

Green Roof Directory

In print for the first time, the Greenroofs.com directory contains more than two dozen companies, categorized by the products and services they offer.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|

Thank you for a very interesting article, which is now bookmarked. I have a question. We are looking to greatly improve the overall energy efficiency of our 1952 build Cleveland Ohio house. As you can imagine this is a very significant undertaking since the house was initially built with *no* insulation in the walls due to the use of knob and tube electrical system that can’t be buried in insulation and single pane windows (Our first winter after we moved in we actually had frost on the *inside* of the walls in our bedroom when the outside temperature dropped below zero. We have resolved that issue by upgrading the electrical system and then injection air-crete into the wall cavities along with a 1.5 inch continuous rigid foam insulation under the siding and a very well taped vapor barrier plus triple paned windows. Now we are looking to improve the insulation of our basement, half of which is finished. But when we do that we want to make sure we also install proper moisture control so that we don’t end up with trapped moisture which can lead to mold and other issues. Given the age of the house I am pretty sure there is no membrane under the floor slab and likely minimal waterproofing on the outside of the walls (likely tar paper and a mastic).

So finally to my question. Should we find that we do have a problem with significant moisture coming through the slab, is there method to inject a waterproofing liquid under the slab? This question came to me since we just had the concrete floor in our detached garage leveled by mudjacking. I wondered if it might be possible to inject a liquid (viscous enough to not just drain down into the fill under the slab, but not so viscous that it creates any significant upward pressure on the slab) through small holes drilled in the slab that would spread out under the slab and then cure to an impervious layer. A center plug in the end of the injector would creates a slot so that the injectant is forced to flow radially outward (at least initially) and hopefully shear between the bottom of the slab and the fill. Even if it didn’t do a perfect sealing job, it might create enough of a barrier to make the moisture problem manageable.

Thanks for your time. Best Regards,

Jim Felder