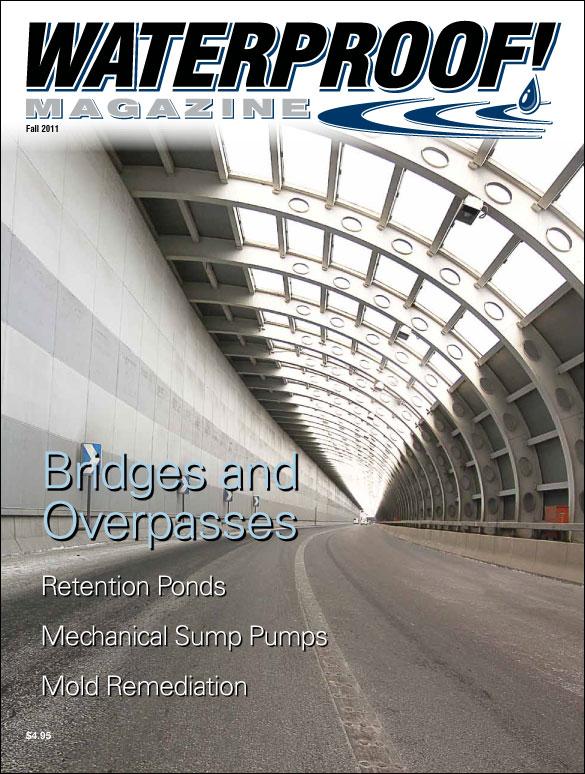

A modern mix of sealants, membranes, and flashings are used to ensure that a bridge’s road deck can withstand the harsh environmental conditions they’re exposed to.

Bridges and overpasses are a critical part of North America’s infrastructure. But they’re an aging part of our infrastructure, which creates an opportunity for waterproofers.

Most of America’s bridges and overpasses were built in the mid-20th Century, when increasing automobile traffic, coupled with Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway Act, created a road-building boom. These structures are nearing the end of their design lifespan, and it’s anticipated that waterproofers and bridge repair contractors will see significant work in the coming decade replacing or extending the operational lifespan of them.

As of December 2009 (the most recent data available), 12% of the more than 600,000 bridges in the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) inventory were classified as Structurally Deficient with an additional 13% declared functionally obsolete. The fact that one of every four bridges in America needs significant repair work was hammered home in a dramatic way when the I-35 bridge spanning the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis collapsed under the weight of rush hour traffic in 2007.

The Bridge Challenge

Bridges are engineering marvels, not just for the distances they span or the loads they carry, but also for the harsh environmental conditions they must contend with. Heavy loads, temperature fluctuations, road salts, and inadvertent oil and gas spills are just a few of the factors that can make even new bridges show accelerated deterioration.

A modern mix of membranes, coatings, sealants, and waterstops are used to help these structures safely carry traffic for as long as possible.

While all parts of a bridge—from the footings and piers to the surface of the road deck—use specialty products to keep water out, this article will focus on waterproofing the road deck.

Layers of Protection

For the vast majority of bridges and overpasses, the bridge deck is built as two separate layers. The lower structural deck is typically high-strength, steel-reinforced concrete designed to last the life of the bridge. The upper deck, or wear surface, is designed to be replaced every few years.

A representative at BASF’s bridge and transportation division, says “Bridge decks require protection from chloride ion intrusion from de-icing salts, as well as freeze-thaw cycles and traffic erosion over time. [There are] a wide variety of products to protect bridge decks, ranging from water repellents to thin polymer overlays. The ultimate goal is keep the deck free of deterioration, keeping it sound and safe for years to come.”

Waterproofing is typically installed as a “split-slab” system, between the wear surface and the structural deck.

Protection begins during initial construction. Most bridges built in recent decades use epoxy-coated rebar instead of plain red iron. Sacrificial anodes are attached to the rebar mats for cathodic protection—so that naturally occurring electrical currents will erode the anode and not the bridge steel.

After the structural deck is in place, it is sealed with spray membranes, sheet goods, or some combination of the two for additional protection. Finally, after the actual road surface is in place, an additional layer of water-repellant sealer is applied.

The road surface is usually asphalt, which is cheaper and lends some degree of flexibility to the roadway. Concrete lasts longer, but it’s more prone to cracking, and isn’t reuseable.

Regardless of the road surface,

Regardless of the road surface,

normal traffic and temperature fluctuations will inevitably lead to cracking. These cracks provide an entryway for water and other contaminants, so all cracks—large and hairline—must be sealed to ensure the long term integrity of the deck.

Most highway departments perform crack repair at least annually, and often provide a complete resurfacing to ensure no moisture reaches the underlying structural deck.

Most road decks use “split-slab” waterproofing. After the structural concrete is in place, it’s carefully sealed. Here’s how a crew sealed the Grant Street Bridge in Gary Indiana:

1 – Seal and detail joints with a combination of fluid-based products and reinforcing membranes.

2 – Prime the entire bridge deck

3 – Apply flashings to all penetrations and edges.

4-5 – Working from both edges towards the middle, carefully roll out the waterproofing membrane. This crew used heat to seal the membrane to the deck and ensure leakproof seams

6 – With the waterproofing complete, the deck is now ready for the “wear course.” This job was completed in the fall of 2008

Split-Slab Membranes

One popular membrane for split-slabs on bridges is Antirock, a thermofusible SBS sheet membrane developed by Soprema. The product is composed of a synthetic, non-woven geotextile impregnated and coated with SBS modified bitumen. It’s heat-applied (torched-down) to the structural road deck to provide a long-lasting protection layer.

According to Jim Wallen, midwest district manager at Soprema, “There’s all kinds of waterproofing out there, but Antirock is specifically designed and tested for bridge applications. It’s used on bridge approaches, spans, and anywhere else the primary purpose is to keep the salt and water out of the structural steel.”

The company offers a companion brush-on polyurethane product for detailing thresholds, sidewalls, and drainage areas.

“The main difference with our product is that its 180 mils [4.5 millimeters] so it’s a thicker, heavier duty sheet for withstanding sustained traffic,” says Wallen. “In fact, the sheet comes with a granulated surface on one side, and if needed can withstand vehicle traffic if they go slow and don’t turn sharply.”

Installation is fairly typical. After spray-applying an asphalt-based primer, the Antirock is unrolled parallel to the direction of traffic flow. Crews work from the edges of the road toward the center line so that the seams are lapped properly. After the membrane is torched down, crews can detail drains and sidewall transitions.

The company makes a machine to aid the torchdowm process. A jet of warm air dries the concrete surface of the bridge, while a burner throws a flame on the back of the membrane to create a solid bond with the substrate. Finally, a roller applies pressure to create a smooth and uniform surface.

Antirock, a bridge deck membrane made by Soprema, was used on the recently completed Beijing Zoo bridge in China. Completed in 2007, it used 27,000 sq. ft. of membrane.

Wallen says the machine makes the work go four times as fast as working by hand, and uses 75% less propane.

“But the real advantage,” Wallen says, “is that it’s possible to repair potholes or even replace the entire wear surface without needing additional waterproofing.”

“When there’s an asphalt-based overlay, you can go in and remove it, scarify the asphalt and the waterproofing layer doesn’t have to be replaced. Properly installed, it will last fifty years or more.”

Fall 2011 Back Issue

$4.95

Options for Retention Ponds

Mold Remediation: An Update

Waterproofing Bridges and Overpasses

Mechanical Sump Pumps

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Options for Retention Ponds

Retention ponds are used for storing everything from stormwater to mining slurry. Others are used at refineries and sewage treatment plants. It’s absolutely essential that the pond liner be waterproof despite the often corrosive nature of the contents.

Mold Remediation: An Update

The excitement and litigation boom centering on mold and mildew has subsided, but the risks have not. Fortunately, new products and construction methods make it easier than ever before to ensure that your waterproofing jobs stay out of court.

Waterproofing Bridges and Overpasses

A modern mix of membranes, coatings, sealants, and waterstops help these structures stand up to heavy loads, temperature fluctuations, road salts, and harsh environmental conditions.

Mechanical Sump Pumps

Instead of electricity, this new sump pump relies on the pressure and flow of groundwater to provide power, eliminating electricity, batteries, and all the worries associated with them.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|