Pressed for space, campuses on both coasts have found room to expand their athletic fields by building stadiums and practice fields on roof tops.

About ten years ago, the University of California San Diego’s East Campus in La Jolla began considering an intriguing project.

The university originally envisioned a parking structure with more than 1,200 stalls on seven or eight levels. However, the project was to be built on a steeply sloping canyon site with unforgiving soil. Further complicating the build, the school wanted to build a soccer/athletic field immediately adjacent to the structure and wanted the building to keep a low profile due to the scenic and ecologically sensitive nature of the area.

The winning design/build team—Bomel Construction Co. and International Parking Design— presented a plan to build two adjoining structures (instead of the owner’s proposed single building), putting the soccer/athletic field on one roof to compensate for the larger footprint. This met the university’s parking needs while allowing for a more-aesthetically pleasing facility, and stayed within the allocated budget.

This design-build project includes two parking structures with a total of 1,229 parking spaces on a steep hillside.

Completed in 2011, the end result is a two-level garage (called the East Structure) with 290,150 sq. ft. (428 parking spaces) and a rooftop synthetic-turf soccer field and archery range. The adjacent West Structure is five levels high, with 819 stalls and 216,000 sq. ft. Both are built with post-tension cast-in-place concrete.

The $24 million project is just one of the many unusual parking structures the Orange County, California concrete contractor has built in recent years. In the case of the UCSD East Campus project, the scope of construction involved much more than building two side-by-side, poured-in-place-concrete parking structures. Jay Smith, principal architect at UCSD says, “We threw a lot of curves at them. The adjacent medical center had a lot of scope that we had to add to the project without sacrificing the schedule.”

The location of the canyon site, which is visible from the heavily traveled Interstate 5 freeway, was also a challenge.

Other members of the design-build team included Wolf Architecture, Hope Engineering, RBF Consulting, Syska Hennessey, PB&A and Spurlock-Poirier.

Cliff Smith, president of International Parking Design, says “If you tried to use the building to hold the earth back, the forces on the building would become greater than the seismic load, therefore the potential for the earth to push the building downhill is immense.”

So instead they used soil-nails to hold the earth in place. They then poured a 40-foot-high retaining wall that runs 240 feet. In addition to being more seismically stable, this design allowed a light well to be created, bringing natural light into the structure.”

Smith, at IPD, says a good working relationship between the key players was critical for project success. “Bomel was able to quickly establish that our designs were going to be within the budget set by the university,” he said. “We have a great understanding of the way they work.”

Despite the difficult conditions, numerous changes in the scope of work, and inovative rooftop practice field, the project was completed on time and within the established budget.

UCSD’s Smith, who has been in the construction industry for 40 years, says “As busy as I am, I really appreciated Bomel’s expediency.”

“We ran into a number of unknown conditions, which tends to impact the schedule,” he added. “In my experience, it could have thrown a lot of contractors for a loop and they’d ask for months and months of an extension. But Bomel didn’t and got it all done professionally and maintained the schedule.”

Rival East Coast High Schools Unite To Create One-Of-A-Kind Athletic Facility

Roosevelt Stadium is built on top of New Jersey’s Union City High School. Directly below the artificial turf is a three-court gymnasium that seats 2,400 spectators, an auditorium, and the cafeteria.

In 2003, the New Jersey School Development Authority—a state agency that authorizes funding to special-needs districts—granted the Union City School District nearly $180 million to consolidate two aging but well-maintained high schools, Emerson and Union Hill, into one shiny new facility.

But where to build? Few options existed in Union City, considered the most densely populated municipality in the United States. The most logical piece of land—a two-block chunk owned by the district—was home to decrepit Roosevelt Stadium, which opened in 1937.

Faced with no other option than to demolish the stadium that hosted decades of games between the schools in an uptown/downtown rivalry, representatives from the school district and architectural firms HOK in New York and RSC Architects in Cliffside Park, N.J., came up with a novel plan: build a three-story school on the site but place a 2,200-seat synthetic-turf football, soccer and baseball stadium on top. The stadium’s portion of the budget was $15 million.

Completed in 2010, Union City High School’s Roosevelt Stadium—one of only a handful of rooftop athletic fields in the country—stands as a tribute to its predecessor, with a classic grandstand roof, arched entries and the old facility’s original signage. And, at three stories up, it may just offer the best seats in all of New Jersey.

“The views are incredible,” says Jeannette Segal, a senior project manager at HOK. “They probably are the best of any high school stadium in the country. You can look out and see the Empire State Building.”

The sideline grandstand holds 2,200 spectators, and there’s room for another 1,800 temporary seats for football games in the baseball outfield.

Roosevelt Stadium, which also will meet some of the community’s recreation needs, and the high-tech school itself represent an urban success story in one of New Jersey’s poorest school districts, according to Union City School District superintendent Stanley Sanger.

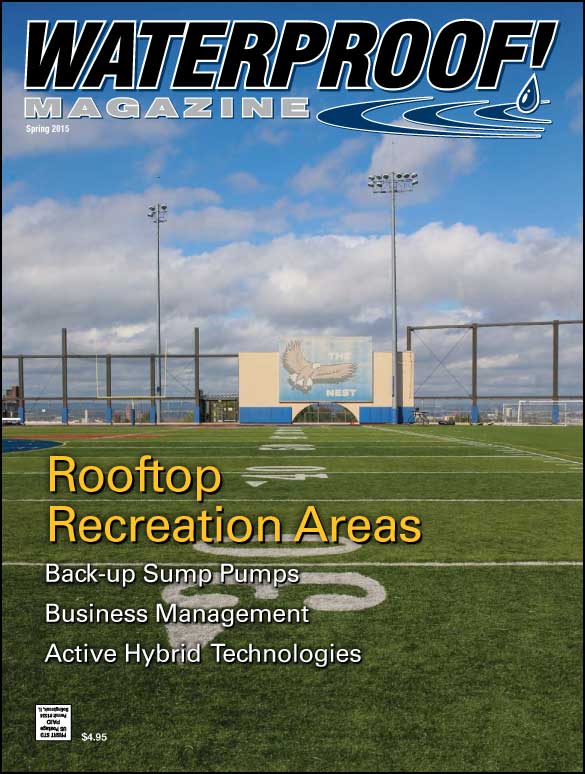

The stadium has been nicknamed “Eagle’s Nest” in honor of its new mascot, a soaring eagle. It seats 2,500 and has artificial turf.

At first glance the new Roosevelt Stadium appears similar to other large high school stadiums. But situated 28 feet off the ground, it has unique challenges and obstacles that Union City High officials are still learning to overcome. There is a 40-foot high net in each end zone to catch field goals and extra points. Since the first game in 2009, only two footballs and one soccer ball have been lost, according to Athletic Director Dave Clauser.

The facility is regularly at capacity, and draws other events as well. The Seattle Seahawks and San Francisco 49ers have both practiced at the stadium prior to games in New York.

This portion of the article was taken from the January 2010 issue of Athletic Business magazine. Reprinted with permission.

Spring 2015 Back Issue

$4.95

Active Hybrid Waterproofing Technologies

Back-up Sump Pump Systems

Rooftop Recreation Areas

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Active Hybrid Waterproofing Technologies

By Stacy Byrd

This new non-curing, self-sealing technology makes it easier than ever to confidently waterproof difficult areas. It’s already been used on several landmark products.

Back-up Sump Pump Systems

By Blake Jeffery

Every home with a sump pump should have a reliable backup sump pump system to protect from problems such as power outages, switch malfunctions, and clogs.

Rooftop Recreation Areas

By Michael Popke

Pressed for space, campuses on both coasts have found room to expand their athletic fields by building stadiums on top of existing buildings. Obviously, waterproofing was a major concern.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|

Project Team

- Owner: Union City Board of Education

- Developer: Summit Redevelopers LLC

- Contractor: Epic Management Inc.

- Architects: Rivardo Schnitzer Capazzi

- Structural Engineer: Harrison-Hamnett PC

- Consulting Engineer: Morris Johnson & Associates Inc.

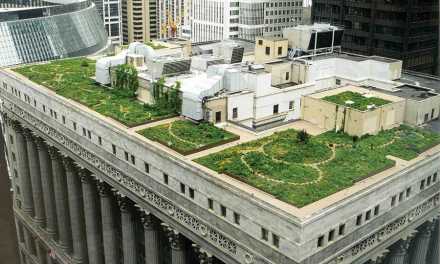

Rooftop Recreation: The History

The two projects featured here are one of a handful of rooftop athletic stadiums in the United States. There are striking similarities in the design of these projects, and while nearly all use synthetic turf, the waterproofing and drainage components are very similar to traditional green roof applications.

Perhaps the first rooftop athletic field in the nation was built at Georgetown University in Washington D.C. In the 1970s, with football attendance dwindling and campus space at a premium, they demolished their stadium and replaced the field by placing Astroturf on the roof of the then-newly constructed Yates Field House.

Designed to hold about 2,000 fans, the stadium was completed in 1979. After more than 20 years of rooftop play, the football team moved back to a conventional field in 2002. But the rooftop playing surface still sees heavy use. According to the athletic department, the northern third of the field is used by the soccer team; the remainder is unused due to structural concerns with the roof.

Perhaps inspired by the Georgetown facility, St. John’s University in the Queens borough of New York City built an elevated soccer facility at the turn of the present century. (Georgetown and St. Johns compete in the same athletic conference.)

Discussions for the St. John’s stadium first got serious in 1996, after the men’s soccer team won the NCAA National Championship that year. When Maxine and Jerome Belson stepped forward with a generous financial gift, the last obstacle was solved and on Feb. 1, 2001, construction began.

The field is situated on a raised platform with parking underneath, and seating for just over 2,000 fans. Completed for the 2002 season, Belson Stadium is considered one of the best college soccer venues in the nation. Artificial lighting, private suites and a press box were added in 2004.

The St. John’s soccer facility, in turn, was one of the inspirations that led to the Union City High football/soccer/baseball stadium atop their high school, which was then in the planning stages.

Brian Stricker, project manager for Epic Management Inc., the general contractor for the Union City High School build, says “It was an unusual approach, but it was really the only solution for this site.” Even with the owner’s blessing and a highly qualified team in place, he admits “we were all somewhat wary in the beginning.”

Taking cues from the green roof movement, the robust deck is supported by dozens of 100-ft-long, 10-ft-deep steel trusses. A key part of the design was water drainage, “which became a technical issue,” Stricker says. “We consulted with green roof designers and with waterproofing consultants on best practices.” In the end, they used drainage and waterproofing courses very similar to systems used on vegetated roof systems. Construction began in 2007, and as with any inner-city project, space at the jobsite was at a premium. “Working in tight places like this presents a lot of logistical and staging challenges,” Stricker says.

The roof is 4.5 acres and includes seven light stanchions for night games and 40-ft-tall nets on each end of the field to prevent field-goal kicks from landing downtown.

From the field’s rooftop vantage point, the horizon is framed by the Manhattan skyline to the east and the Watchung Mountains to the west. “When people are up there, they are in awe,” Stricker says.