by Vanessa Salvia

Water is heavy. Four feet of water exerts nearly 300 pounds of pressure per square foot of wall.

This pressure, called hydrostatic pressure, is the force of water pressing against slabs or walls below the water table. A basement footing with 10 feet of saturated soil above it must withstand 600 pounds of pressure per square foot. This force, obviously, is strong enough to buckle walls and otherwise wreak havoc on concrete and anything else foundational if that pressure isn’t released by moving the water away from the wall somehow. Furthermore, that pressure is enough to damage and eventually wear away some coatings or waterproofing membranes.

To properly protect a concrete foundation, the wall must be both sealed against the water, and the water must be moved away from the wall.

There are two ways to seal a wall: One is dampproofing (asphalt liquid applied membrane) and the other is waterproofing (spray rubber membrane). Typically, dampproofing is done for residential foundations because it is much cheaper on a per square foot basis than waterproofing membranes.

There are a few ways to relieve hydrostatic pressure. The most common way is to channel the water to the foundation footing, where a drainage pipe collects the water to move it away. “More and more, builders are choosing dimple board instead of spray tar,” says Sean Bahr, technologist at DMX. “Although dimple board is slightly more expensive than tar, the savings in time to install makes it almost equal in cost.”

Although asphalt (spray tar) is still applied in the majority of residential foundations, it has disadvantages. It is less effective than waterproofing, can flake off the foundation after it reacts with the chemicals in soil and it cannot be sprayed on in rain or in below-freezing temperatures. Unlike asphalt, dimple boards do not emit any harmful fumes or effluent so they do not pose any health risk to the contractor.

Dimple boards are a more comprehensive and better way to protect the concrete foundation than spray tar. “Dimples create an air gap between the soil and concrete foundation. Therefore, if water comes over the membrane, it falls safely to the footings without any hydrostatic pressure pushing the water against the concrete foundation,” explains Bahr.

Waterproofing sprays are typically polymer modified rubber sprays that are applied in thicknesses of 40 mil or more depending on the application. The higher the polymer loading, the better the waterproofing capability of the coating. After the waterproofing membrane has been applied, it needs to be protected against backfill and/or hydrostatic pressure in the soil and the most common method of protection is with the use of drainage boards.

As the depth of the foundation increases, the drainage boards require a higher compressive strength due to the increased pressure of the soil. Drainage boards have a fabric on the dimple side which drains the water from the soil. By draining away the water, the hydrostatic loads on the membrane and foundation are lessened considerably.

The DMX Drain drainage board is made of polypropylene, which is highly resistant to chemical interaction and has a life expectancy of up to 50 years when properly installed. And because the polypropylene is so strong, it provides the foundation with a measure of protection if the contractors are less-than-careful when backfilling around the foundation.

These dimple boards not only work vertically; they can also be used on concrete decks. “You have a concrete plaza deck and you waterproof it, then you put the drainage board on top to protect the waterproofing and provide a drainage layer,” explains Harold Hays, waterproofing technical services manager for Mapei. “That drainage layer gives a path for water to migrate to a drain.”

Mapei uses polypropylene for the dimple board, where other manufacturers sometimes use the less sturdy polystyrene. Though they don’t manufacture drain pipes, one product, Mapedrain TD (Total Drain), is used in place of the traditional French drain at the base of the wall

“This is a great choice for blindside applications, cut and fill poured in-place foundations or pretty much any time a French drain is needed,” says Hays. “The product is probably a little bit more expensive than your traditional French drain assembly which consist of filter fabric, #57 stone and a 4-inch perforated pipe. But you can lay 100 feet of this in the same amount of time that you could lay 10 feet of your traditional French drain, so it reduces your labor costs and that really helps the installer or contractor.”

In Mapei’s system, Mapedrain, a drainage composite (another word for drainage board) with a three-dimensional core and polypropylene fabric, covers the whole wall. “All the water that’s collected in the Mapedrain will drain down to the TD collection system,” says Hays.

Downspout extensions will keep water from collecting near the foundation, and are an important part of drainage solutions in areas with significant rainfall.

Hays says in the Southern California area, a French drain is commonly called a burrito drain. The TD system replaces the burrito drain system, in which the Mapedrain covers the entire foundation wall and turns out on the footing, which the burrito drain sits on top of. “So when your water runs down it’ll migrate into that drain,” he says. “Our TD, like other manufacturers’ collection drains, has fittings that go along with it, to turn corners, splice sections together or hook a 4-inch pipe to it through a side out connection, to pipe it out to daylight or to a sump pump area.”

Which system to use, the TD or a French drain, according to Hays, is personal preference, akin to whether you like to drive a Chevrolet or a Ford. “It does the exact same thing,” he says. “Some architects really have not warmed up to the flat pipe technology as we call it. They still like using the traditional French drain.” Often, the French drain is used in residential applications because it’s a cheaper material, even though, as Hays asserts, saving money in labor during installation does save money in the long run.

While it might seem counterintuitive, good foundation waterproofing doesn’t start at ground level. It starts with the rain gutters at the eaves of the rooftop. “Given a single inch of rain, a 1,000-square-foot roof will produce 600 gallons of water,” says Austin Werner, president and owner of The Real Seal LLC, a basement crack repair and waterproofing company in Schaumburg, Illinois, who is also a member of the Basement Health Association. “And 1,000 square feet is not that much. If your gutter extensions end next to your house and it rains three inches, you’re talking thousands of gallons of water being poured right next to your house and undermining your footing.”

As that water cascades down, it washes away dirt. It can then take thousands of dollars to pier a house back up. Werner has seen numerous examples of homeowners who cut off the underground extension for their gutter because they didn’t think it was working and allowed the water to pour next to their house. “And two or three years later the house starts sinking,” Werner explains. “It’s like quicksand.”

Werner doesn’t recommend systems where drains are installed on top of footers. “Some places actually sell top of the footer systems and they are not a good option in our professional opinion,” Werner says, “because by the time the water hits that pipe, it’s right at the floor level. So if we get torrential rains there’s no way it can keep up.”

Unfortunately, there’s no standard limiting the sale of these systems, and people are able to install many of these systems in their own way. “The ICC standard for drainage systems is actually just gravel without any pipe,” Werner says. “And then it’s up to the municipalities, the states, the cities, the townships and counties in order to expand on that code and to make it as they want. So in Chicago for instance, you must use perforated pipe. You move five miles west out of the city and it’s corrugated perforated pipe.”

Unfortunately, there’s no standard limiting the sale of these systems, and people are able to install many of these systems in their own way. “The ICC standard for drainage systems is actually just gravel without any pipe,” Werner says. “And then it’s up to the municipalities, the states, the cities, the townships and counties in order to expand on that code and to make it as they want. So in Chicago for instance, you must use perforated pipe. You move five miles west out of the city and it’s corrugated perforated pipe.”

The best use case is that drainage placement is next to the footing. As Werner explains, if it’s on top of the footing, there’s usually only approximately four to eight inches of space between the top of the footing and the foundation floor. “And if you put a four-inch pipe within a gravel bed on top of the footing, by the time the water level hits that pipe in order to be drained it’s already flooding your basement,” he says. Below the footing is non-optimal as well, because in that scenario you’ll wash out the dirt under the footing as you move water, which could compromise the structural integrity of the foundation.

Dörken System Inc.’s Delta-MS wall waterproofing is designed as a residential foundation protection system where there is a low water table—which is, of course, where most people choose to build. Delta-MS is an HDPE dimple membrane that protects foundation walls using the air gap that’s created in between the membrane and the wall to eliminate hydrostatic pressure.

Dörken’s Delta-MS dimple board is unique in that they are co-extruded in three different layers and take advantage of the properties of both virgin and recycled HDPE. “We have a top layer of virgin polyethylene, a center layer of recycled polyethylene and a bottom layer of virgin polyethylene,” explains Peter Barrett, product and marketing manager for Dörken in Ontario, Canada. “Anything that is 80 to 100 percent recycled material simply doesn’t last. It doesn’t stand up to the pressures and the dimples collapse over time. This is why the Delta-MS product is made from 60 percent recycled and 40 percent virgin materials.”

In any construction, whether it’s commercial or residential, a cold joint is a point that is vulnerable to failure. A cold joint is where one part of the concrete has been poured and cured and then more concrete is added to it so it’s not a continuous pour. This is just one example of why you wouldn’t place a perimeter drain on the footing. “Because now you’re guiding the water down and collecting it right at the point of high risk and you’ll end up with hydrostatic pressure on that cold joint, which you don’t want. For this reason, you should always put the foot of the perimeter drain beside the footing, and never on the footing.”

Dimple membranes create an air gap between the membrane and the wall to eliminate hydrostatic pressure.

Vanessa Salvia is a freelance writer specializing in the construction industry. Based in Eugene, Oregon, her work has appeared in numerous national and regional publications.

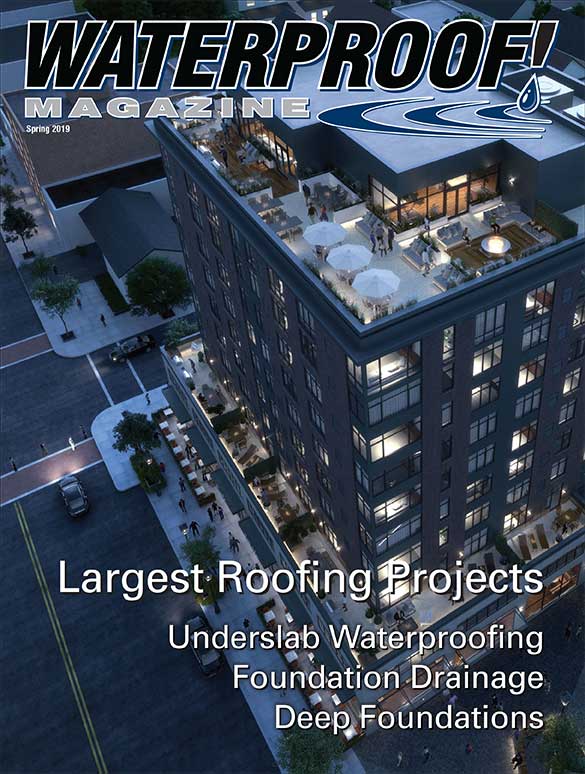

Spring 2019 Back Issue

$4.95

Drain Tiles and Footing Drains

Roofing America’s Largest Buildings

Options for Underslab Waterproofing

Waterproofing a Deep Foundation

AVAILABLE AS PDF DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Drain Tiles and Footing Drains

By Vanessa Salvia

Sheet drains, perforated pipe, and other products are used to create systems to collect moisture and route it away from the foundation without the risk of clogging.

Roofing America’s Largest Buildings

By Vanessa Salvia

The largest roofs in the U.S. have been completed with a number of different materials, including single ply membranes, spray-on coatings, and even green roofs.

Options for Underslab Waterproofing

In choosing an underslab moisture barrier, permeance is only one of the variables in the equation. The sheet’s tensile strength, puncture resistance, and other factors may be even more important.

Waterproofing a Deep Foundation

By Greg Maugeri

Sealing the deep foundation on this high rise apartment building near New York City presented a host of challenges. Integral crystalline waterproofing greatly simplified the job.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | PDF Downloadable Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|