Data shows that sealed crawlspaces dramatically outperform traditional dirt-floored ones. The choice between concrete and plastic depends on geography, soil, and the occupant’s plans for the space.

Why seal off a regular dirt crawlspace? Well, sealed crawlspaces are dryer, healthier, and far more energy-efficient than regular ones. Over the past few years, sealed crawlspaces have become increasingly common; the two methods most frequently used to seal the floor are concrete slabs and flexible plastic membranes. Whether the floor is dirt, concrete, or the most high-tech polymer lining, each affects the living area above it.

Advantages of Sealing

A traditional dirt-floor crawlspace with industry-standard venting has several disadvantages. The root cause of these disadvantages is moisture in the unconditioned air. In the summer, warm moist air comes in contact with the cool conditioned floor above it and condenses, which can cause mold, wood rot, and attract pests. In the winter, unconditioned air steals heat from the living area, driving up energy bills.

Adding more vents to circulate more outside air through the crawlspace doesn’t fix the moisture problems but actually makes them worse. That’s because of the “chimney effect”—warm air from the crawlspace is literally sucked into the conditioned living area due to pressure differences. And in today’s tightly sealed homes, these odors and health threats can build up in the living areas.

Up to 40% of the air on the first floor of a home comes from the crawlspace. It often contains mold spores, radon gas, and musty odors. In addition to being unpleasant, this air can be downright unhealthy. Common symptoms include headaches, fatigue, coughing, sinus congestion, sore throat, and eye irritation.

“The number one reason a homeowner seals a crawlspace is simple,” says Lou Cole, owner of Emecole. “It is a wet, musty breeding ground for mold.” Emecole is a provider for basement waterproofing contractors and crawlspace sealing professionals.

Ultimately, sealing the crawlspace (eliminating the outside vents and lining the ground and walls with a vapor barrier) has been found to be the best solution to crawlspace problems. (See Closed Crawlspaces in the Spring 2011 issue.)

Drainage must be addressed before the barrier is installed. Often, this means bringing in and leveling a layer of pervious fill.

In 2005, Advanced Energy conducted a study in North Carolina that quantified the advantages of closed crawlspaces. Homes with liners saved 15% on heating and cooling and were much drier than those with dirt crawlspaces, with average humidity below 70%. In 2009, they conducted additional tests in Baton Rouge and Flagstaff to see how a sealed crawlspace would perform in extremely humid and extremely dry climates.

“In Baton Rouge, the results were very clear that closed crawl spaces dramatically affect relative humidity,” says Cyrus Dastur, building scientist at Advanced Energy. The closed crawl space systems in Louisiana kept crawlspace humidity around 60% (as opposed to 80% in dirt crawlspaces). In Flagstaff’s dry climate, even dirt crawlspaces had less than 70% humidity, but the closed crawl spaces were even drier, with levels around 50%.

Energy savings in Flagstaff were dramatic. Closing the crawlspace and adding floor insulation saved nearly 20% on winter heating and 15% in summer months. The study also showed decreased levels of radon, mold, and other allergens.

Sealing the Space

Mike Trotter, owner of Trotter Company, a Georgia-based waterproofing company, says closing crawlspaces is a great way for waterproofing contractors to diversify their businesses. “I believe crawlspaces are a great business to get into,” says Trotter. “Virtually, every crawlspace needs to be closed and lined.”

Sealing the crawlspace involves several steps, including closing off the air vents, sealing the dirt floor, and installing dehumidifiers, insulation, and sometimes a drainage system. In some instances, mold remediation and/or pest control is also needed.

The key component of the system, though, is sealing off the moisture coming through the dirt floor. Is concrete a good choice, or is a plastic liner better?

Concrete

At first glance, pumping concrete into a crawl space may seem logical to homeowners. After all, concrete slabs work well in the garage and basement. Additionally, it creates a nice finished look, and provides level, convenient storage.

But sealing and insulation experts say it may not be the best choice for air quality.

Ron Greenbaum, owner of Nash Distribution, an Ohio-based waterproofing wholesaler, has sealed hundreds of basements over the years. “Concrete is a good option in new construction, but it’s often not a good choice for retrofit applications,” he says.

“As long as there are stable soils, and if it’s poured properly, it should be fine. The problem is that in retrofit jobs, often you have very limited space and it’s just hard to work in, and that affects being able to pour the concrete right. Also, if the soil is contaminated, you’ll need a liner. If there are oils or radon in the soil, you’ve got to have something under that concrete.”

Cole is adamant that concrete is never a good choice for retrofit jobs. “Choosing wet, porous concrete to seal a crawl-space is like hiring a wolf to guard the chicken coop,” says Cole. He claims the water in the concrete mix—50 to 75 gallons per cubic yard—will add to a home’s moisture problems.

“I realized pumping concrete into the crawl space was actually a disservice to the homeowner,” he says. “Cosmetically it may look great, but the concrete required for a 1,000 square foot crawlspace with a 4-inch slab contains 500 gallons of water, which will be entrapped within the floors and walls of the home,” he says, “especially if there’s a liner underneath the slab. All that moisture can only escape upward.”

Even after the concrete is completely cured, Cole says it can continue to contribute to moisture problems. Without a thermal break, the temperature difference between the warm moist air and the cold concrete surface will cause condensation. And that leads to more mold.

Greenbaum says that the condensation issue can be avoided by insulating under the slab. The Barrier, an insulated underslab moisture barrier from Northwest Ohio Foam Products, is a perfect solution. It consists of a 3/8” core of flexible EPS foam sandwitches between two 3-mil polyethylene sheets. It combines thermal barrier, a vapor retarder, and moisture barrier in a single product.

Cole is unconvinced. “A homeowner who agrees to have concrete pumped into a crawl space is unknowingly saturating the entire area with mold-friendly moisture,” he says.

Liners

The alternative to pumping concrete is installing a polyethylene liner or membrane.

The 2005 and 2009 studies cited above demonstrated that the minimum thickness required to stop the moisture is a 6 mil polyethylene liner (1 mil is equal to 1/1000 of an inch.)

Most crawspace liners look the same. They’re usually string-reinforced white polyethylene. Dario Lamberti, product manager at Insulation Solutions says most customers prefer white because it offers a clean, aesthetically-pleasing space. “If they’re using it for storage, or even go down there at all, they’re going to put in some lighting, and that white liner makes it look so much more appealing,” he says. “It really cleans it up.”

Tom Saucier, owner of Crawlspace Doctor in central Indiana, says that while a 6-mil barrier is adequate, thicker is often better. Most commonly a 12- to 20- mil product is used, but liners up to 90 mils thick are available. It depends on how much use the crawlspace is going to see. “If installed properly any liner is going to work,” Saucier says. “The question you have to ask is ‘How are you going to use the space after it is finished? Do you ever want to see it again?”

Thicker membranes are more durable, but some of them can be difficult to install, especially if the crawlspace is tight or has multiple piers.

Saucier says, “A 10-mil liner will keep out the moisture just the same as a 20-mil liner as long as it is installed properly and it will be cheaper for the customer.”

Greenbaum explains, “Thicker liners are a little harder to install around piers. Some of the heavier ones feel like you’re laying carpet. So if there isn’t going to be any storage, a thinner 10-mil barrier is good enough”.

On the other hand, if the crawlspace is relatively spacious with outside access,. homeowners will frequently use the area for storing boxes and other items. (Trotter, the Georgia waterproofer, met one customer who had five canoes stored in his crawlspace.)

Greenbaum says that most of his clients in the upper Midwest do plan on using the space to some degree, so he usually installs a thicker 20-mil barrier. “Whatever thickness you choose,” he says, “make sure it’s inorganic—so mold won’t grow, and puncture proof.”

Lamberti says insulation Solutions makes a cross-woven, reinforced 10-mil liner that can stand up to significant abuse. “It is available in other thicknesses,” he says, “However, because of the crosswoven reinforcement, it’s going to have equivalent strength characteristics to higher millage products.”

Every barrier manufacturer prepares a spec sheet for their products—it’s usually available online—which the installer can use to verify the liner is anti-microbial and fire-retardant.

In any case, the barrier should at a minimum:

- Permanently seal the floor

- Be treated for mold and mildew resistance

- Be easy to detail around piers and wall edges

- Be capable of stopping radon and other natural gasses in the soil

The Next Step

As noted earlier, sealing the floor of the crawlspace is just one part of closing the crawlspace. Greenbaum notes that if physical water is present, a drainage system is mandatory, and must be installed before the liner. Frequently, he installs a sump pump in the lowest area of the space.

“Also, I always recommend dehumidification,” he says. “Make sure the system is big enough to take care of the square footage and still be efficient. You don’t want it to have to run all day long.”

Cole adds, “In sealing crawlspaces, it’s important that we do it right. We can take the easy way out, or we can take a more educated approach. A little education can save lives.”

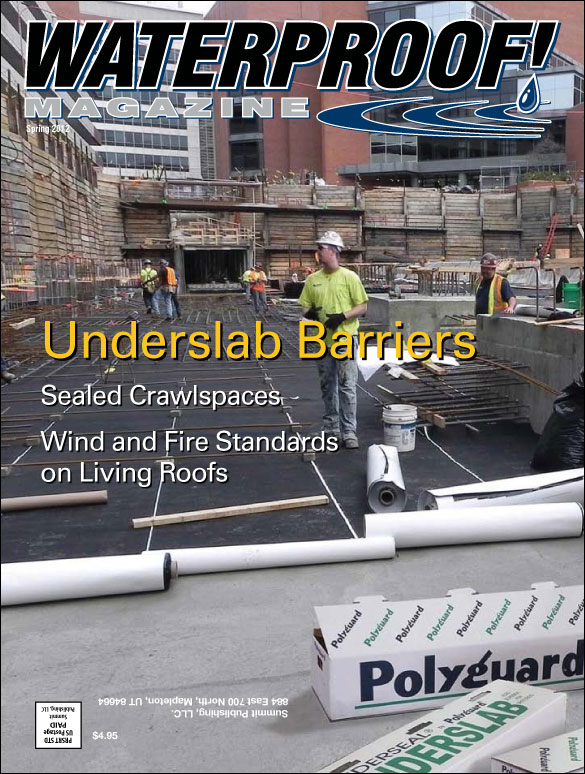

Spring 2012 Back Issue

$4.95

Underslab Barriers: Does Millage Matter?

Wind and Fire Standards for Living Roofs:

Taking Your Business Commercial

Sealed Crawlspaces: Concrete vs. Plastics

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Underslab Barriers: Does Millage Matter?

The thickness of an underslab moisture barrier is frequently used as a gauge of performance. But other factors, such as tensile stregnth and puncture resistance are just as important.

Wind and Fire Standards for Living Roofs:

By Kelly Luckett

New standards define what’s needed to keep living roofs safe from wind damage, and prevent the spread of fires. They also prove that green roofs have overcome the final hurdle for acceptance by the design community.

Taking Your Business Commercial

By Melissa Morton

Project size, opportunities, ad profits are all larger in the commercial sector, but so are the risks. Three contractors who have made the leap successfully discuss what you need to know before your residential waterproofing business starts bidding on commercial work.

Sealed Crawlspaces: Concrete vs. Plastics

The new trend in basements is to seal crawlspaces from outside air and soil moisture. The two most popular methods to seal the floor each have unique considerations that if not considered may aggravate moisture problems.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|

Living in the country we have gophers who create inroads for rats. Not lovely. I don’t see a vapor barrier stopping gophers. Seems best solution is vapor barrier with a thin ratslab…