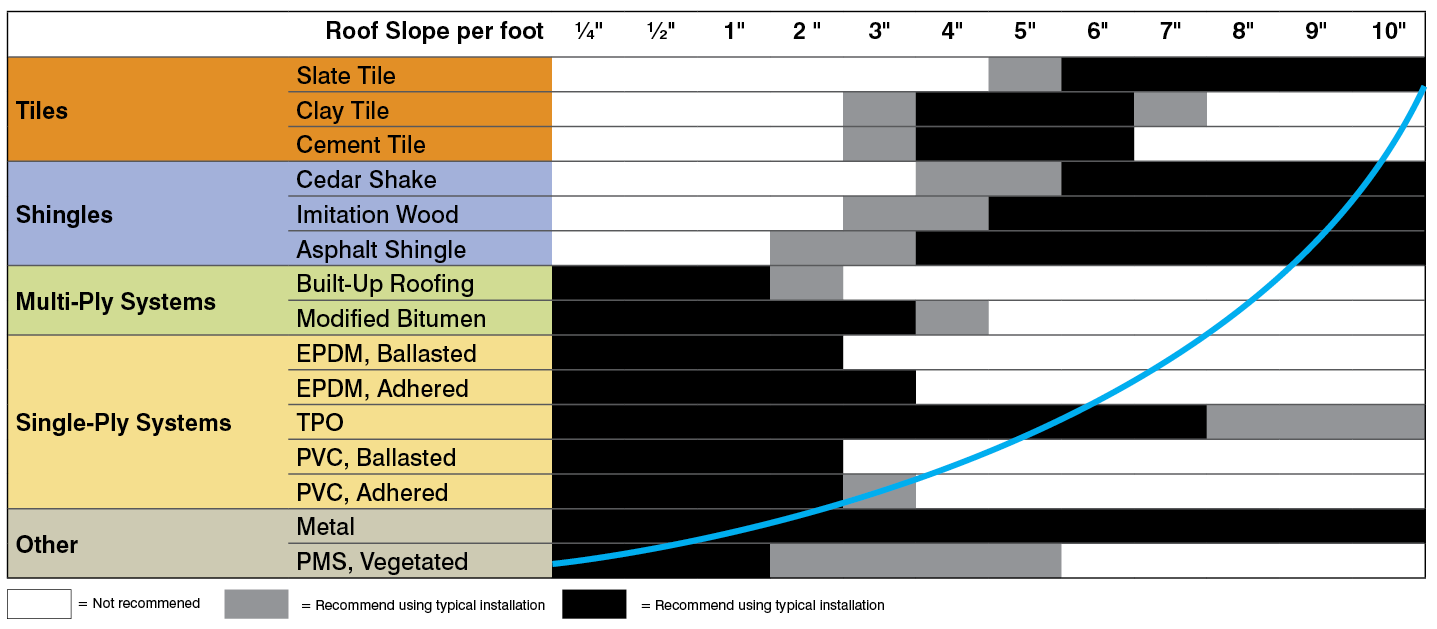

The optimal roofing product for a building depends primarily on a roof’s slope and weight-bearing capacity.

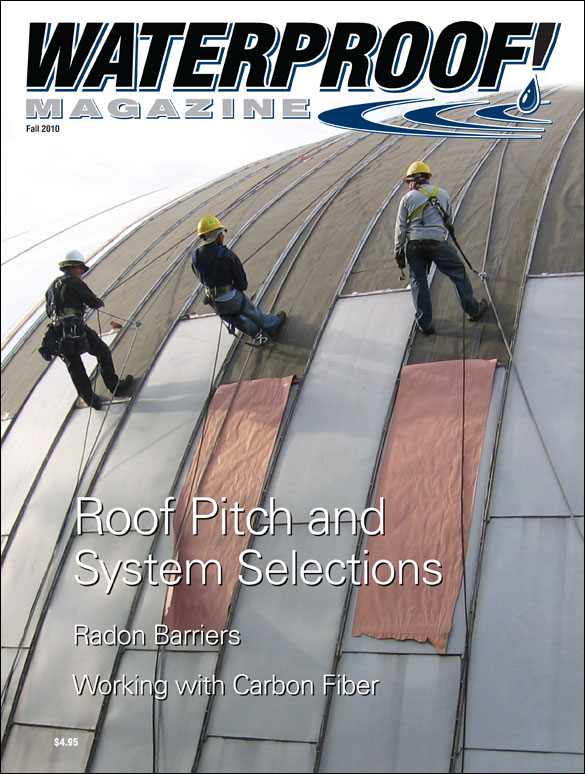

With a pitch that varies from dead flat on the top to near vertical at the eaves, metal roofing was a good choice for this building.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the roof is the most vital part of the building envelope, and therefore, the most critical investment. It’s also no overstatement to say that we now enjoy a wider range of roofing materials and roofing system than at any other time in history.

However, not every roofing system works in every application. Finding the right system involves weighing a multitude of variables including cost, weight, lifespan, maintenance requirements, and most importantly, aesthetics. In recent years, environmental factors such as recyclability, sustainability of raw materials, and roof temperature have also become major considerations.

Of all these variables, roof slope is perhaps the most important. It affects drainage, maintenance requirements, and materials used more than any other single factor. It is considered the primary factor in roof design. It also has a major impact on the finished style of the building, whether it’s a steep-pitch sloped roof visible from street level, or a low-slope roof design with less visual impact.

An understanding of the major commercial roofing systems—and how their performance is affected by roof slope—is critical to maximizing the effectiveness of the covering.

Roof Pitch

The slope, or pitch, of a roof is typically expressed as the amount of vertical rise (in inches) for every foot of horizontal length along the gable. A roof with a rise of six inches per foot would be called a 6/12 roof.

Conventional slope roofs, with a pitch between 4/12 and 9/12, are the most common in residential work. Roofs with a pitch exceeding 9/12 (37 degrees) are termed steep slope roofs.

In commercial work, low-slope roofs (with a pitch between 2/12 and 4/12) are most common. Roofs with a pitch of less than 2/12 are considered flat, even though they technically have some slope. The minimum allowable slope for drainage is ¼” per foot.

Steeper sloped roofs are generally more visually pleasing and tend to last longer, as the water runs off immediately and ice damming is avoided. However, they also cost more because of the additional materials required to build them, and are impractically tall for larger buildings.

Roof material selection is highly dependent on roof slope. For instance, single-ply or torch-down roofs are not appropriate for high-slope applications. On the other hand, visually appealing roofing products such as shingles or tiles do not work well on low-slope roofs.

Additional Factors

Of course, roof pitch is not the only factor in system selection. Often, the weight of the roof plays a deciding factor. Vegetated and ballasted roofs, for instance, can put a significant load on structural elements. Similarly, roof underlayment and insulation can eliminate some roofing materials from consideration. Hot-applied or torch-down roofing is not compatible with rigid foam insulation.

The Army Corps of Engineers estimates that 75% of the roofing industry consists of reroofing existing structures, so issues such as construction noise, fire hazards, fumes, and building access can also come into play.

Shingles and Tiles

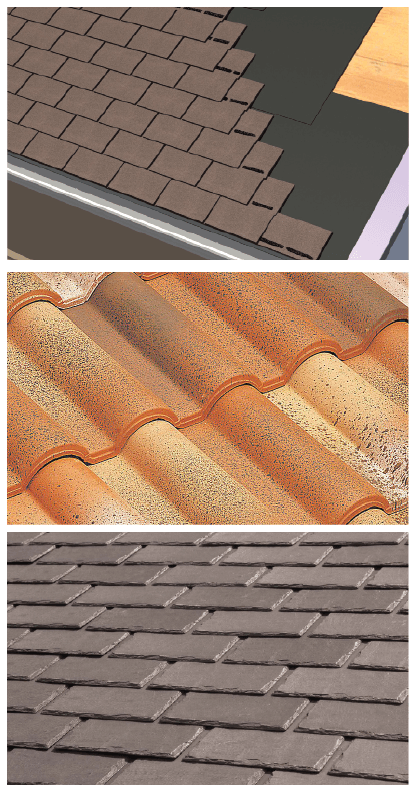

For steep and conventional pitched roofs (4/12 and above) shingles and tiles are an attractive option that perform well. Asphalt (top) is most economical. Tile (middle) provides a long-lasting roof with little maintenance. Synthetic wood and slate (bottom) are durable, long-lasting, and appear identical to the natural materials they imitate.

For conventional and steep-slope roofing, shingles and tiles are the best way to go. They have been used for roofing for hundreds of years, and are still a great choice for conventional roof pitches.

Clay tiles and natural slate have a proven track record stretching back centuries, and modern products will last a lifetime if properly applied. Warranties of 75 years are not uncommon. The primary drawback to tiles is their cost and weight. Clay tile runs $6 to $10 a square foot in most areas of the country. Real slate is at least double that.

Concrete roof tiles are available at prices similar to clay, and can imitate both slate and clay tiles. They’re typically warranteed for at least 30 years.

All three products, clay, concrete, and slate, weigh between 900 to 1,200 pounds per 100 square feet, so the roof deck and supporting structure must be able to support this additional weight.

Wooden shingles are also an option. Cedar is surprisingly durable; since they don’t bend, they withstand strong winds and hailstorms better than their asphalt counterparts.

Recently, imitation cedar and slate roofing has come on the market. EcoStar, a leading manufacturer of this type of product, offers their Majestic Slate and Seneca Cedar roof tiles in nine colors and five styles. Made from 80% post-industrial recycled rubber and plastic, they’re flexible, durable, and indistinguishable from traditional materials once installed.

“These are an environmentally friendly, lightweight alternative to traditional slate and cedar roofing products,” says a marketing manager for the company.

With a weight comparable to wood shakes, they don’t require extra structural support. They are, however, quite expensive, priced around $10 per square foot plus installation costs.

Asphalt shingles are the most commonly used roofing material in North America. They’re economical, versatile, and work well on most residential roof pitches. They’re easy to install, relatively long-lasting, and available in virtually any color and style an architect could desire. Asphalt shingles are likely the most affordable roofing option for moderate and steep sloped roofs, running between 50 cents to $1.50 per square foot. They weigh at least 250 pounds per 100 square feet, on the light end for roofing materials.

According to industry website Roofingkey.com, the main drawback to asphalt shingles is related to the service life. “Asphalt roofing shingles are available in grades with an expected life of 20-50 years depending on the price. However, durability issues and wear-out or material failures occur earlier than expected in some situations.”

It should be noted that unlike the other products mentioned so far, asphalt shingles can be used on low-slope roofs with a pitch between 2/12 and 4/12, but they require special underlayments and installation techniques to handle ice damming and other water issues.

Metal roofs are perhaps the most versatile system

Metal Roofing

The two most common metal roofing materials are painted aluminum and steel. Copper and stainless steel are also metal roofing options, but their cost is high enough that they’re seldom used.

Aluminum has become a top choice because it does not rust, it muffles the sound of rainfall, and can simulate cedar shakes, tiles, and slate.

Metal can be used as a roofing material on any roof pitch. For low-slope structural roofing, standing seam roofing is generally used. Some low slope metal roofing requires machine seaming during roof installation to ensure a watertight seal. A seaming apparatus is simply rolled along the panels to crimp the panel seams together.

Metal roofs have a long service life compared to other low-slope roofing options. A 2005 study conducted by Ducker International found that respondents expected metal roofs to last 40 years –17 years longer than built-up and 20 years longer than single-ply systems.

Typically, metal roof systems weigh from 40 to 135 pounds per 100 square feet, making them among the lightest roofing products. Because metal roofing comes in large panels, it’s also among the easiest to install.

In summary, metal roofs can provide easy installation, a long service life, low maintenance requirements, light weight, and meet sustainability and recyclability concerns.

Ballasted roofs have a proven track record, and help prolong the life of the membrane.

Built-Up Roofing

The vast majority of commercial and institutional buildings have flat roofs, and for much of the 20th Century, that meant using a multi-ply Built-Up Roofing (BUR) system. Sometimes called a “mop-on” or “tar-and gravel” system, it uses a combination of roofing felt, tar and gravel. The felt is installed in three-foot rolls, and the layers adhered together with hot asphalt, bitumen, or coal tar. A final gravel surface is broadcast over the final layer of asphalt for UV protection, worker safety, and to reduce fire danger.

A modified bitumen system (MB or SBS) uses a propane torch to seal the layers together instead of hot asphalt.

Single-ply systems (discussed below) have captured a significant share of the market, but with nearly 150 years of proven performance, BUR systems are still preferred by many building owners and operators as a proven and viable method. A 2006 study by RSI magazine found that various forms of BUR still held 35% of the new construction market.

Built-Up roofs use a series of layers adhered together with hot tar or heat from a torch.

BUR systems are not especially heavy; gravel roofs weigh 400 or 500 pounds per 100 square feet, smooth roofs weigh about half that.

BUR is occasionally used in residential applications, but working with hot bitumens is not recommended on roof pitches exceeding 1/12. Modified Bitumen (torch-down) systems can be used on roof pitches up to 3/12.

Keep in mind that because BUR membranes are installed using hot asphalt, tar or torches, any insulation near the roof assembly must be heat resistant. Finally, workmanship is critical, because BUR is field assembled.

Single-Ply Membranes

In the last two or three decades, a number of new materials have been developed that have proven perfect for waterproofing flat roofs. Unlike multi-ply systems, these roofing systems require only a single layer, and are more forgiving of imperfect workmanship. The three major types of single-ply roofing are EPDM, TPO, and PVC.

EPDM—The oldest of the single ply products is EPDM, which stands for Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer. Invented in the mid 1960s, it’s basically a durable rubber sheet ranging from 30 to 90 mils.

The product is rolled out over the roof deck, and adjusted to the proper overlap, usually marked right on the roll. Most modern EPDM roofing comes in rolls with a factory-applied adhesive on one edge of the roll. The factory-applied tape is laid into the primed overlap and rolled with a little pressure. The resulting seam is strong, perfectly straight, and unlikely to fail.

Single ply systems, like this EPDM installation, are perfect for flat roofs. Recent innovations, such as self-taping seams, make them even more durable and long-lasting.

EPDM roofs are now lasting 30 years or more; seams and penetrations are usually the weak point. The membrane can be fastened to the roof deck three different ways. It can be mechanically fastened, or “fully adhered,” meaning completely glued down. It’s also used in “ballasted” systems, where the membrane is “loose-laid” over the roofing area and held in place by a thick layer of gravel poured over the top. None of these systems require heat, so EPS insulation can easily be used.

Rubber EPDM membranes are easy to install and very durable.

EPDM roof membranes are readily available in white or black, although other colors such as tan are offered from a few manufacturers.

EPDM is a low cost solution for flat roofs. Ballasted roofs are unfeasible above pitches of 2/12, although mechanically fastened and fully adhered systems have been used on slightly steeper pitches in areas where winds are not a problem. EPDM roofs are lightweight, except when ballasted; then they weigh in at 1,000 lbs per 100 sq. ft.

TPO—One of the newest types of single-ply roofing products is TPO, or Thermo-Plastic Olephine. Instead of being a rubber like EPDM, TPO is a plastic. It’s more expensive than EPDM, but has significant advantages.

“What makes TPO great is its ease of installation and its heat-welded seams,” says Thomas Kral at Reliable American Roofing. “In addition, TPO is available in rolls larger than other roofing systems, which means less seams. And less seams means less chance for failure.”

TPO is available in multiple colors, but it’s usually white. White TPO is highly reflective and meets U.S. Department of Energy standards for a cool roof without additional modification. Because TPO roofs may qualify for tax credits and LEED points based on their color, they’re seldom used for ballasted systems. It’s nearly always installed mechanically fastened or fully adhered.

TPO has heat-welded seams, which translates to a lower risk of leakage.

Mechanically attached systems should not be used on steep roofs in windy areas; fully adhered TPO systems are suitable for all roof pitches and weather conditions.

PVC—Like EPDM, Poly-Vinyl Chlorate (PVC) has a long track record of success as a roofing material. It’s slightly more expensive than TPO; however, installation methods are almost identical. It also uses heat-welded seams, which form a permanent, watertight bond that is stronger than the membrane itself.

It’s also considered environmentally friendly. Nearly all regions of the U.S. have established roof recycling programs that converts scraps or old membrane back into new product. Also, just 47% of the PVC resin’s raw materials are derived from petroleum, less than any other single ply roofing membrane. (The remaining 53% are derived from salt.) Finally, PVC roofs are naturally fire retardant due to their chemical composition and have better fire ratings than competing products.

White-colored roofing material like TPO and PVC can dramatically reduce energy costs.

They do have drawbacks, however. PVC is incompatible with petroleum-based roofing products, and should not be used in direct physical contact with EPS insulation, asphalt, coal tar pitches, or where coal tar fumes are present.

Also, most manufacturers recommend limiting PVC to roofs with less than a 2/12 pitch.

Vegetated

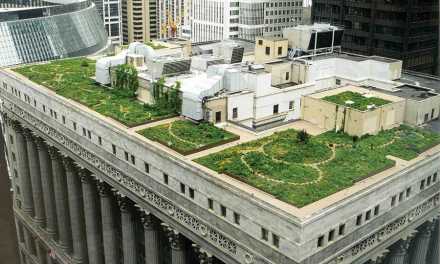

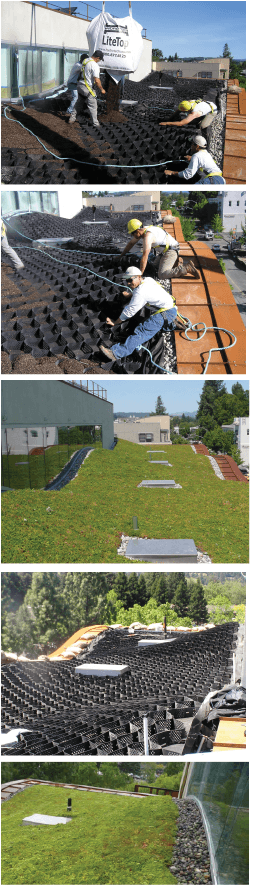

Vegetated roofs can now be installed on slopes previously unsuited for the technique. Located atop the H2 Hotel in Sonoma, California’s wine country, this roof used GardNet from American Hydrotech to hold growing medium in place

Vegetated, garden, or green roofs have skyrocketed in popularity over the past decade. Traditionally, they have been constructed using the same techniques used for ballasted or protected membrane system (PMS) roofs. That’s limited their use to roofs with a slope of 2/12 or less; at higher pitches, the growing medium becomes unstable.

However, within the last two years a new product has come on the market to take green roofs places previously thought impossible. GardNet, marketed by American Hydrotech, is made from perforated polyethylene strips, fastened together to form an offset grid that holds the soil or growing medium in place, even on considerable slopes. It’s available in standard depths of 3 to 12 inches. Each section, measuring approximately 8 feet by 20 feet, holds several dozen soil retention pockets, about a square foot each. The large sections are secured into place with a network of steel cables, which are adequate support for roofs up to a 7/12 pitch.

The system has been used on a number of high profile projects, including the headquarters of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Fall 2010 Back Issue

$4.95

Underslab Radon Barriers

Working With Carbon Fiber

Roof Pitch and System Selection

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Underslab Radon Barriers

In some areas of the country, radon barriers—a variation on the underslab moisture barrier—are a great way to improve the livability of the building and add additional income to the company’s bottom line.

Working With Carbon Fiber

Stronger and less bulky than steel, carbon fiber is making basement structural repair easier than ever before. Whether its carbon straps, staples, or sheets, we explain what the options are, and how to make sure they’ll perform.

Roof Pitch and System Selection

Flat roofs obviously require different treatment than steep ones. We’ll look at the role roof pitch plays in determining how a rooftop waterproofing membrane will perform.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|