Interior Drainage Systems Can Eliminate Damp Basements

A range of products are available to dry out and repair wet basements with minimal excavation.

By nature, a basement is difficult to waterproof. A porous concrete structure built into the ground is set up to leak.

“Basements are not designed, intended, or built to be boats,” said Joseph Boccia, vice president of Boccia Inc., a New York-based waterproofing company that has completed thousands of projects. “Concrete will not naturally keep water out. Submerged in water, they will eventually leak. This fact has been putting food on my family’s table since 1955. So, if you can’t seal out the water, then you have to drain it. This is where interior basement drainage comes in.”

Hollow baseboard products divert seepage to the sump pump with zero excavation needed.

These drainage systems collect water before it can enter the basement, and redirect it to a sump pump. “If there’s no water outside, there won’t be any water inside,” Boccia says simply.

Installed on the interior side of the footing or basement wall, these interior drainage systems greatly reduce the mess and expense associated with repairing leaky basements.

Melissa Morton, an editor at the Basement Health Association, says, “There are many different systems with different details but the concept is the same: collect the water that comes into the basement, control it, redirect it, and pump it out.” She explains that interior drainage systems can be categorized by the location of the drain tile and whether the system is open or closed.

Location Of The Drain Tile

The three common locations of the drain tile are: on the slab, on the footing, and beside the footer.

Ken Cotten, owner of Waterproof.com, markets a full range of interior drainage products. “We approach waterproofing as good, better, and best,” he explains. “It comes down to what elevation that you’re doing the waterproofing.”

In the vast majority of cases, water entering a basement comes in through the walls. (Occasionally, a high water table will force water up through cracks in the middle of the floor, but Cotten describes this as “very, very rare,” and is beyond the scope of this article.) So the question becomes, at which elevation does the drainage system capture this water?

The least expensive are on-the-slab drain tiles that collect water at the joint where the wall meets the floor. These “hollow baseboard” product are simple enough some homeowners install them themselves. It simply collects the water coming in through the cove joint and channels it to the sump pit.

Emecole, a basement repair supply company based near Chicago, Ill., markets this type of product, as does Waterproof.com. Boccia’s Hollow Kick Molding also falls into this category, although it’s usually combined with a perforated pipe to create a deep channel system.

Lou Cole, owner of Emecole, points out that in addition to saving money, baseboard systems mean less mess. “There’s no need to break up floors, compromising structural integrity, as a simple in-floor groove is all that’s needed to install the baseboard and divert seepage to the sump pump,” he says. “This system can be used with block, stone or poured foundation walls.”

On-Footer Systems

Another class of drainage system sits on top of the footer. It’s a nice compromise that controls the water before it reaches floor level, but also eliminates the need to dig a deep trench.

When a drain tile is already in place beside the footer, and all that is needed is a more efficient system for moving moisture from the inside face of the wall to the drain tile, dimple products are a great choice. Drain-EZE and Hydro-Channel are designed specifically for this applications.

Cotten says, “Instead of collecting the water above the slab, you’ve gone down four inches, and are collecting water from above and below the floor in a single profile.”

On-footer repair profiles can include its own conduit or consist of a simple diverter.

If the drain tile is clogged or missing, other products can provide water collection and a conduit to move it to the sump pit and still fit on top of the footer. Examples include Drain-Main and VersaDrain.

These products are usually made from heavy duty PVC or polyethylene to provide exceptional flow rates and withstand the weight of the concrete pour.

Installing an on-footer drainage system requires removing four or five inches of concrete floor slab adjacent to the exterior walls, and replacing that part of the slab with new concrete once the product is in place.

Deep Systems

Sub-slab or deep channel systems are considered the best option for saturated soils or failed drain tile. The floor slab is typically removed 12-16 inches from the exterior walls, and a trench is dug beside the footer. A new drain tile is placed in clean gravel, and the concrete replaced. Traditionally, perforated pipe was the product of choice, but other options are now available that claim to move water more efficiently and resist roots and clogging.

Waterproofing contractors debate whether it’s best to install the tile beside or below the footer.

Jason Weinstein, owner of Budget Dry Waterproofing in Killingworth, Conn. says basement floors in older Connecticut houses are traditionally too thin to support an on-the-footing drain system. “My experience has shown that systems installed where they bisect the top of the footing or slightly beneath the top of the footing work with more reliability.”

Joe Boccia, who has spent 40 years keeping homes and businesses dry, says, “If they are digging a trench, they might as well set the drain tile deep enough to relieve hydrostatic pressure. Sub-floor drainage systems relieve the hydrostatic pressure that builds up outside of the wall and below the basement floor.”

Dan O’Conner, of HydroArmor Waterproofing Systems in Woolwich Township, New Jersey, agrees deeper is sometimes better. “The trench needs to be deep enough and wide enough for the pipe to be set where the water is,” he says. “The drainage system also needs to be a continuous system to channel the water.”

Boccia explains how his company’s Hollow Kick Molding product works: “A deep channel filtered perforated pipe relieves the hydrostatic pressure that would have pushed the water into the building envelope. Then we drain any residual water with our patented Hollow Kick Molding which protects and enhances the appearance of the floating slab cove detail. This gives us the opportunity to guarantee the job for the life of the structure.”

Cotten markets a competing system called Fast Track. It’s rigid, which makes it easier to hold a level line; and has no corrugation, so it doesn’t collect sediments and allows water to flow more easily. The trapezoidal shape moves small amounts of water quickly, but as water volume builds up, the capacity of the drain tile increases proportionately. He claims this product requires “a lot less labor, with less digging and hauling heavy fill in and out of the basement.”

Open vs. Closed

Historically, basement drainage systems were left as an open system. Any water that built up on the inside of the wall would be able to drain down into the system and to the pump. Many waterproofing contractors still use this philosophy. Open systems have a floating slab with a gap—typically ½” to ¾”—around the perimeter of the basement between the floor slab and the foundation wall.

“An open system was the way the waterproofers installed their drain systems,” says Hugo D’Esposito of A.M. Shield Waterproofing.

The drawback to open systems is that while they allow moisture to go down, they also allow radon and other soil gases to come up into the basement and upper levels of the house.

Closed drainage systems, on the other hand, leave no gap. “These systems can even go one step further by incorporating vapor barriers on the wall and sub-slab fans to remove moisture and other gases,” D’Esposito says. However, closed systems make it more difficult to handle interior moisture problems.

“One group wants to seal the floor, the other wants to drain it,” summarizes Boccia.

In some cases, a new drain tile will be laid beside the footing, along with a system to direct water to it..

One of those groups concerned about open systems allowing pollutants to enter the house is the Basement Health Association (BHA). “The problems in the basement and crawlspace go beyond moisture,” says John Bryant, BHA president and owner of AquaGuard Waterproofing in Beltsville, Maryland. “As basement waterproofing contractors, you have to think about radon, mold and pollutants in the basement air.”

Dave Hill of Spruce Environmental Technologies in Massachusetts says the biggest issue is radon. “You have to understand a radon mitigation system won’t work with an open drainage system,” he says. “The waterproofing system has to be closed in order to deal with the radon issue.”

Radon is a radioactive gas found in some soils. At high enough concentrations, it can cause cancer. “If a waterproofing contractor cuts a gap into the basement floor and then the homeowner develops a radon problem, the waterproofer could be to blame,” Hill says. “It could mean lawsuits for waterproofing contractors.”

To address this issue, Boccia recently redesigned their product to include a vapor retarder which impedes pollutants from entering into the basement environment.

Other hybrid radon mitigation/waterproofing systems use wall vapor barriers and sub-floor fans to move radon out of the living space.

Open vs. Closed

As with all waterproofing jobs, it all comes down to cost. Cotten says simple, above-slab hollow baseboard systems can be as inexpensive as $20 per lineal foot. Other products are significantly more expensive, and labor costs increase significantly as well.

Closed systems are the priciest. “Closed systems are very difficult to install effectively, both from material and labor cost, especially in older homes with stone foundations,” says Weinstein, the Connecticut contractor. “Other costly obstacles to doing closed systems include oil tanks, water heaters and furnaces as each contractor handles these differently and there’s no uniform standard for where and how they are placed in a basement or crawlspace. As awareness about radon spreads through the public, there will be an eventual push for closed drainage systems.”

Closed drainage systems prevent radon and other pollutants from entering the living space. They require vapor barriers on the wall and careful sealing of all terminations.

Still, Cotten says remedial drainage is a profitable niche that’s easy to get into. “When I got into the business, it cost a great deal of money to get into this line of work. Not anymore. We work with the ‘small guys.’ Hybrid products are easy to install, and there’s virtually unlimited growth.”

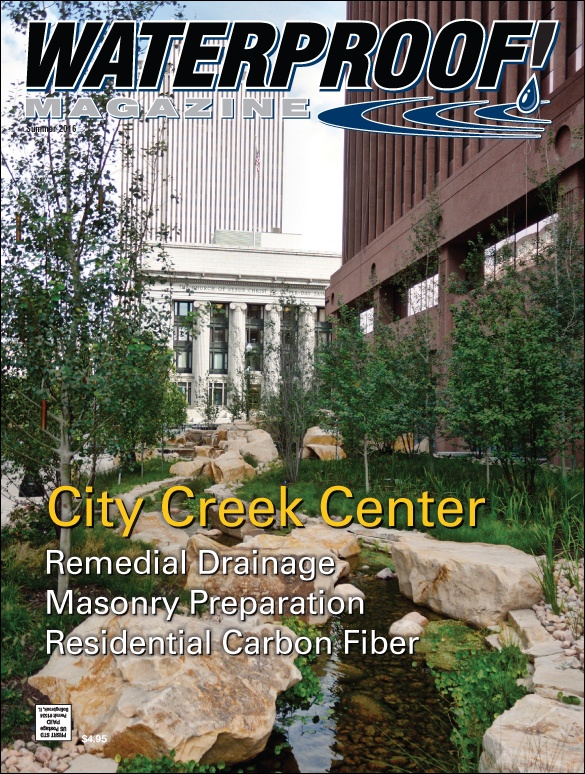

Summer 2016 Back Issue

$4.95

Remedial Drainage Options

Project Profile: City Creek Center

Residential Carbon Fiber

Preparing Masonry for Waterproofing

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Remedial Drainage Options

Wet basements can often be dried out and repaired from the interior. A range of products are available to simplify remediation and make below-grade living spaces habitable again.

Project Profile: City Creek Center

City Creek Center in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah, is one of the largest commercial developments in the U.S. Waterproofing the massive project was challenging, especially as it has a half-mile long creek flowing over the roof.

Residential Carbon Fiber

Stronger and less bulky than steel, this space-age material is making basement structural repair easier than ever before. Available as straps, staples, or sheets, it has been used on projects across the U.S.

Preparing Masonry for Waterproofing

By Don Foster

Sealing a masonry wall preserves it for all to see. A few simple procedures prior to sealing will ensure the structure looks its best for years to come.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|