New and renovated stadiums, such as this soccer arena in Berlin, Germany, pose many daunting challenges. This particular structure was built for the 1936 Olympics. Its restoration included waterproofing nearly 100,000 yards of concrete and protecting the steel in the new roof.

Around the world, athletic stadiums are a profitable specialty for waterproofing companies. Most major cities are either building massive new facilities, or have aging stadiums in need of being replaced or refurbished.

One challenge with waterproofing these facilities is the sheer size of the project. Professional sporting venues often have a capacity of nearly 100,000 people; stadiums that hold more than 50,000 spectators are commonplace on college campuses and elsewhere.

Not only are they massive, but they’re complex and frequently exposed to more weather and abuse than the average building. Everything from the below-ground concrete and parking areas to the deck sealants, roof membranes, façade coatings, and steel corrosion inhibitors, need to perform well—resisting weathering, temperature swings, mechanical wear and abrasion—and also add to the overall ambiance and aesthetics.

Concrete Work

Nearly always, stadium construction begins with placing thousands of yards of concrete. In July, when concrete work for the new Vikings Stadium in Minnesota was completed, crews had placed 100,000 cubic yards. The tons of exposed structural steel, the façade, and the roof will also need extensive waterproofing once in place.

The 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia were remarkable because prior to the Olympics, the area was not really developed. It required building all sorts of infrastructure, from seaports to ski lifts, before work could begin on the athletic facilities. Additionally, most of the construction was built under adverse climate and geological conditions.

Many of the structures built for the Sochi Olympics, such as this ice skating arena, used concrete waterproofed with a crystalline admixture.

“It’s a unique location,” says Robert Revera, president and CEO of The Penetron Group. “Here you have a saltwater harbor on one end of town and an Alpine village at the other.”

Work began with building a modern harbor on the Black Sea. Then, a water treatment plant and a new railway station was built that could accommodate up to 20,000 passengers per hour. Finally, work began on the ice hockey arena, bobsled run, and ski facilities—all built with concrete and needing extensive waterproofing.

Today, the Olympic venues look pristine and perfect, but only because waterproofers were able to overcome significant challenges. The “Russian Hills” Alpine skiing facility, for instance, is located on a geological fault system where the bedrock lies at a considerable depth and the surface is mostly unstable sand. The complex includes a number of buildings that are built partially or completely underground.

Igor Chernogolov, president of Penetron Russia, says “On-site construction and waterproofing was done under the most difficult conditions: heavy rainfall and a high water table from all the melting snow and ice. It soon became obvious that no topical waterproofing solutions would work.”

Additionally, schedules were extremely tight, and the Olympics, of course, could not be delayed.

Penetron makes an admixture that renders concrete waterproof by creating microscopic crystals inside the pores and hairlines cracks. By adding the waterproofing directly to the concrete mix, work was able to proceed on schedule. Additionally, crystalline waterproofing has the ability to “self-heal” and seal hairline cracks that develop after the concrete has cured.

“Sports are a large part of everyone’s lives and modern sports venues enjoy immense popularity around the world,” says Revera. “We’ve done a lot of stadiums over the years.”

Christopher Chen, director of Penetron, says, “Our success on major stadium projects speaks for itself. Our crystalline technology stood behind the Summer Olympics 2008 in China, the FIFA World Cup 2010 in South Africa, and more recently, the Sochi Winter Olympics 2014 in Russia and the FIFA World Cup 2014 in Brazil.”

The skiing and bobsled facilities above in Sochi , Russia, were waterproofed in wet, cold conditions on a tight schedule.

The 2014 World Cup was the biggest event yet for the world’s most popular sport. Preparation began years earlier, when Brazil began construction on 12 new stadiums to hold the crowds that would travel from around the globe to watch the spectacle. Seven of the 12 were waterproofed with a concrete admixture from Penetron.

Arena Castelão, built in the northern coastal city of Forteleza, is something of a showpiece. The 60,000 seat arena was completed within budget and at a “lower per seat” cost than any of the other World Cup stadiums. Located in close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, the project used about 60,000 cubic yards of concrete—all treated with the waterproofing admixture.

Chen says, “Sports complexes like Arena Castelão [not only] provide state-of-the-art training opportunities and attractive venues for events; they also generate a tangible economic impact for a whole region.”

Not all waterproofed concrete ends up in foundations and walls. Penetron reports that a Chinese stadium built for the 2008 Olympics used 10,000 cubic yards of concrete for seating, and a 70,000-seat venue in Cape Town, South Africa, built for the 2010 World Cup used treated precast concrete seating throughout.

The Kleber Andrade soccer stadium, used for the 2014 World Cup, used integral crystalline waterproofing in the concrete used as stadium seating.

Protecting Iconic Structures

Of course, a significant portion of stadium waterproofing is retrofitting existing structures. In the late 1990s, after the re-unification of Germany, the country debated the future of the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Built in 1936 as a symbol of Nazi power, it seated more than 100,000 spectators, and was still the largest stadium in the country. Ultimately, the decision was made to renovate.

In 2000, work began to strengthen the foundations and columns using 96,000 yards of concrete, carefully waterproofed. A few years later, a second round of renovations were launched in preparation for the 2006 World Cup, which included adding a roof over the spectator seating.

“In stadiums two important factors to be considered regarding the steel structure are preventing steel corrosion, which could significantly reduce the structures durability and lifespan, and performance in fire, which could cause loss of structural integrity and endanger life,” explains a Sika case study. The company got the contract to protect the 3,500 tons of structural steel. The solution used a two-part epoxy primer and several layers of epoxy paint, topped with a polyurethane top coat to increase UV resistance and color retention.

Roof repair work on the Louisiana Superdome began with pressure-washing years of dirt, grime, and mold from the membrane.

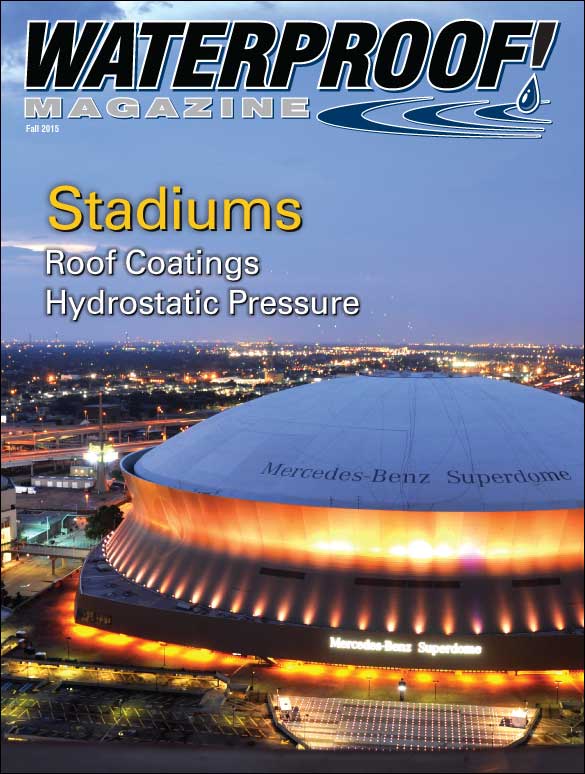

The Mercedes-Benz Superdome in New Orleans is another iconic sports venue that has recently been renovated. At 425,000 sq. ft., it’s the largest dome structure in the world, and is home to the NFL’s Saints, as well as two college bowl games. Like the rest of the city, it was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2004. Restoring the appearance and performance of the white domed roof would be, according to the local Times-Picayune newspaper “the largest roof repair job in American history.”

The key was finding a roof coating that could resist the buildup of dirt and biological growth. Trahan Architects chose eight potentially suitable products and painted 10’x10’ test patches on the roof. They were left to weather up to 10 months to see how they performed in color retention and the ability to resist dirt and mold growth.

In the end, Kymax, a white low-build elastomeric coating from Quest Construction Products was selected for the circular roof. “The goal was to eliminate the need for washing,” says lead architect Brad McWhirter. “The Kymax topcoat is almost self-cleaning. When it rains, it appears to wash itself.”

Brazos Urethane got the nod as roofing contractor, and workers began by pressure washing the 9.6-acre roof to remove existing dirt and growth. Then, they sprayed on two layers of the coating at a thickness of six wet mils each. It cured to a tough, flexible, enamel-like finish that resists abrasion, mold, dirt, acid rain and all types of weather extremes. The material also contains infrared-reflecting pigments, which will reduce temperatures nearly 30%.

A new spray-applied membrane was applied that cured tough, flexible finish that also reduces temperatures by nearly 30%.

The final step in the process—the Mercedes-Benz logo and lettering— presented its own unique set of challenges. This was hand-applied using brushes and rollers.

Now, the Superdome has a new, high performance cool roof with a guaranteed 20-year life.

When the Dallas Cowboys’ wanted to upgrade their home field, team owner Jerry Jones decided to start from scratch. The new AT&T Stadium outside of Dallas is the largest venue in the NFL. Jones wanted to include many of the design elements of the original Texas Stadium, including the famous hole in the roof, and the feeling of an outdoor arena. To accommodate that, the design features a glass skin and a translucent retractable roof. Ground was broken in 2006, and much of the waterproofing is below grade, including the membranes layered between the rock bolts and shotcrete that hold back massive forces 60 feet below the original surface level. The glass façade is comprised of 5,071 glass panels tinted (of course) in a blue-gray hue and weighing more than one million pounds. Reportedly, it required more than 16 miles of silicone caulking to seal the exterior glass into place.

The retractable roof is supported by two massive arches 1,225 feet long and nearly 300 feet high. That meant roofing crews were working more than 350 feet above the playing field.

“Stadium roofs not only need to be waterproof and durable to withstanding the external exposure and physical stresses, they must also fulfill the architect’s design requirements in terms of shape, form, color and overall aesthetics,” says Rick Chappell, an account specialist for Sika Sarnafil.

Sheet membranes were used on the new Dallas Cowboys stadium roof, installed by crews that worked more than 300 feet above ground level.

KPost Company, of Dallas, was the roofing installer. The project involved attaching 660,000 sq. ft. of roofing membrane, which required 1,620 five-gallon buckets of adhesive and more than 350,000 screws.

“The size of the project was monumental,” says KPost project superintendent Thomas Williams. “There’s nothing like it anywhere.” Safety was a major factor; men, tools, and material were all tied off. Williams continues, “The logistics were a nightmare, and all material and tools had to be strapped down due to slope of the roof and high winds.” The 60-mil single-ply PVC roofing membrane came in rolls weighing in at nearly 400 pounds, so it was critical that they be secured.

Chappell visited the jobsite nearly monthly during the installation. “It’s the roofing crews that make it as good as it looks,” he says. “I’m amazed at what these guys went through during installation at 300 feet in the air.”

Williams concludes, “This was a once-in-a-lifetime project due to the size, shape and steep slope of the domed roof.”

Fall 2015 Back Issue

$4.95

Relieving Hydrostatic Pressure

Waterproofing World-Class Stadiums

Fluid Applied Roof Coatings

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Relieving Hydrostatic Pressure

It’s critical for water to drain away from footings. Sump pumps, sheet drains, perforated pipe, and other products must work together for maximum performance.

Waterproofing World-Class Stadiums

From the recently renovated Superdome to new facilities built for the Olympics and the World Cup, these massive projects require extensive waterproofing from the foundation to the roof.

Fluid Applied Roof Coatings

Spray-on roofing membranes can extend the life of a roof by decades without the cost of tear-out and replacement. It takes less time, less labor, and yields a monolithic, seamless, waterproof roof.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|